|

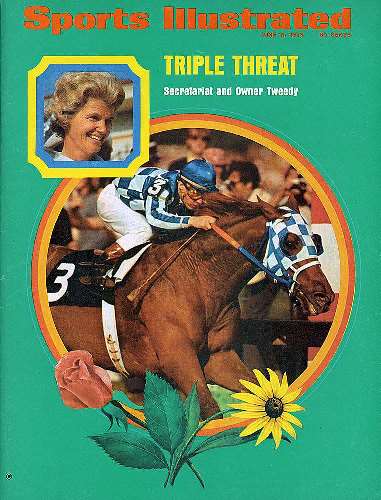

With a dollop of guilt, I read about the plague of layoffs at Sports Illustrated. After all, I dropped my subscription shortly after retiring as a sports columnist at the Times, nearly eight years ago. I no longer needed to keep up with most of the sports; I needed time to read other things. So it’s hard to level blame at the decline of a giant that meant so much to generations of fans and readers. It’s a sign of the times. I have seen very good newspapers decline or disappear. No sense going over the list. Apparently, the economy does not support the printed word you can hold in your hand and read without having advertisements and other diversions slither into your vision. Thank goodness the NYT and Washington Post and Wall Street Journal and others keep up the staffs and budgets and the standards to keep track of the scoundrels in our midst. But Sports Illustrated – once a plush weekly with talent and swagger plus the budget to back them up – has now been sold to something called a digital platform company.  As a young newspaper reporter, I appreciated the writing style -- and space -- that went far beyond the daily accounts in the papers. Stars like Dan Jenkins and Robert Creamer in the early years, Neil Leifer with his camera, always in position, and then young stars like Frank Deford and Gary Smith. It took time to read their articles. These were no tweets, no muscle-twitch fire-the-bum impulses from the Blogosophere. If I had to pick one article that stood for all the expertise and talent (and space, and money) of Sports Illustrated, I would choose the ode to Secretariat written by my friend Bill (William in his byline) Nack, upon the putting down of the great champion in October of 1989. (As it happened, I had petted Secretariat on his swayed back in May, had felt the earth tremble when he moved. ) Bill loved the big red horse, loved the Bluegrass milieu, and he cried when he got the phone call he had been dreading. Later, Bill went through the self-torture of writing he felt every time, only worse this time. But SI had space, and patience, and when Nack was done, there was the article, the masterpiece. But Nack was not alone. Like a Secretariat of magazines, Sports Illustrated raced through more decades of stories and stars: Tim Layden with his versatility, Steve Rushin with his columns, Michael Farber on hockey, Tom Verducci with baseball, Grant Wahl treating soccer seriously, Doctor Z -- Paul Zimmernan - with pro football. So many more I could, should, mention. (Plus, I should note, before SI, there was the great Sport Magazine, RIP, edited for over a decade by my friend Al Silverman, who passed recently. Sport was doing long-form articles long before SI did.) Then the model began to show its age. Advertisements declined. Attention span declined. People were slinging opinions over the Web. Instant gratification. I’m old. I don’t know 99 percent of what goes on out there in the Web. I get the New Yorker in print form every week, and peruse it ceremoniously, and The New York Times arrives in my driveway every morning, plus its magnificent website, and if I want to find out what my Mets did in the past 24 hours I consult Newsday (paid) or the New York Post (on line.) Plus hard-covered books, all over our house, plus magazine articles friends send me. More than enough to read. Hence, my tremor of guilt about the imperilment of Sports Illustrated. Then I read about good people, whom I knew when they were youngsters just breaking in, like Chris Stone, the editor-in-chief, who just got fired by the “digital platform,” whatever that is. Bill Nack cried over Secretariat. I just shake my head and write this piece…and put it out there…on line. Thanks, Sports Illustrated, for all the great articles over the years. * * * Bill Nack's masterpiece on the death of Secretariat, standing in for all the glorious long pieces in SI: https://www.si.com/longform/belmont/index.html NYT article on the talent massacre at SI: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/03/business/media/sports-illustrated-layoffs.html?searchResultPosition=1 A list of great writers at SI: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Sports_Illustrated_writers The time I petted Secretariat, courtesy of a friend: https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/category/horse%20racing In the fall of 1988, our son and I went to Lincoln Center to see a revival of "Waiting for Godot."

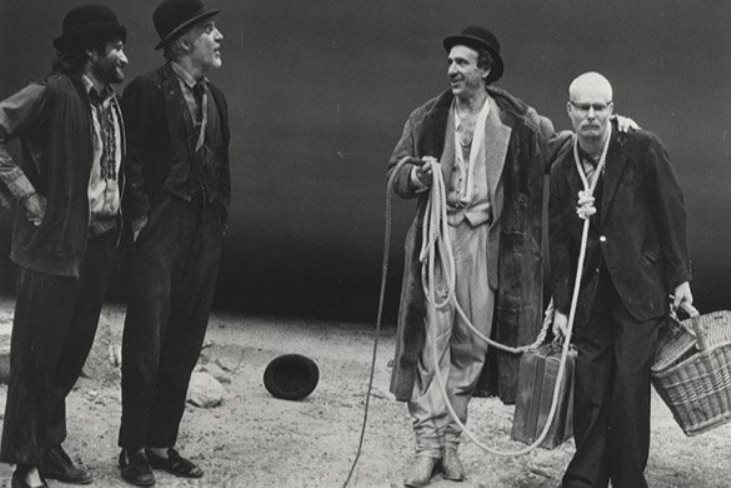

Robin Williams and Steve Martin were quite fine in the two lead roles, and F. Murray Abraham was properly domineering as Pozzo, leading his abject slave, Lucky, played by the master kinetic actor, Bill Irwin. I was thinking of that master-slave relationship Friday night when The New York Times broke the story that the FBI had begun an investigation in early 2017 of the apparent master-slave relationship between Putin and Trump. www.nytimes.com/2019/01/11/us/politics/fbi-trump-russia-inquiry.html In the real-life version, Lucky snarls and yaps at just about everybody else, but when Pozzo fixes his Lubyanka-basement glare at him, Lucky rolls on the floor and whimpers. How did poor Lucky come to be led around on a leash? Beckett does not say. I am hoping this will soon be explained to us by Robert S. Mueller, III. It is beginning to dawn on me that President Trump is not merely some bloated orange spectacle from a reality show.

He is consciously presiding over the demolition of health in the country. The New York Times ran one of those special public-interest sections on Thursday, the kind they seem to produce regularly – a Pulitzer-worthy section of the week. This one was on the environment – in many of the corners where I used to work as a news reporter, including the Kanawha River in Almost Heaven, West Virginia. The lead article is by Eric Lipton and John Branch, a great reporter with whom I had the privilege of working for a few years. John is based in his home state of California, and he already won a Pulitzer for his work on the science of a murderous avalanche. Branch is a member of the sports department but they rarely send him out to cover games; he’s part of the direction the Times is going – important journalism being committed on a daily basis. (Yes, I miss baseball box scores and daily Mets coverage, but would choose the vital journalism being produced by the Times these days.) Branch and Lipton write about the farmlands of Kern County, Calif., one of the major agriculture centers in the country. Since Trump was inaugurated in January of 2017, in front of those yooge crowds in Washington, he has facilitated dozens of downgrades of environmental practice. The Times documents them in this section. The presidential approval of pesticides in the vegetable garden of America could be poisoning you, wherever you are, but it is certainly sickening the workers – many of them brown and Spanish-speaking – the braceros, the obreros, who pick your lettuce, when they are not fainting and vomiting from the poisons Trump has let loose. The children's day-care center is downwind from the sprays. The pesticide, named Chlorpyrifos -- why, look here, it’s from our old friend Dow Chemical -- belongs to a class of chemicals developed as a nerve gas made by Nazi Germany, as Nicholas Kristof wrote in a Times column in 2017: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/10/28/opinion/sunday/chlorpyrifos-dow-environmental-protection-agency.html Kristof added that the nerve gas is “now found in food, air and drinking water. Human and animal studies show that it damages the brain and reduces I.Q.s while causing tremors among children. It has also been linked to lung cancer and Parkinson’s disease in adults.” This poison is now being sprayed all over Kern County, killing insects and sickening humans and also enriching the companies and the politicians that enable this toxic man. Congratulations to the newspaper and web site that grow more serious and more invaluable all the time. Here’s the on-line version of the article by John Branch and Eric Lipton: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/12/26/us/politics/donald-trump-environmental-regulation.html “Bertolucci died,” my wife said, checking the pinging on her smartphone.

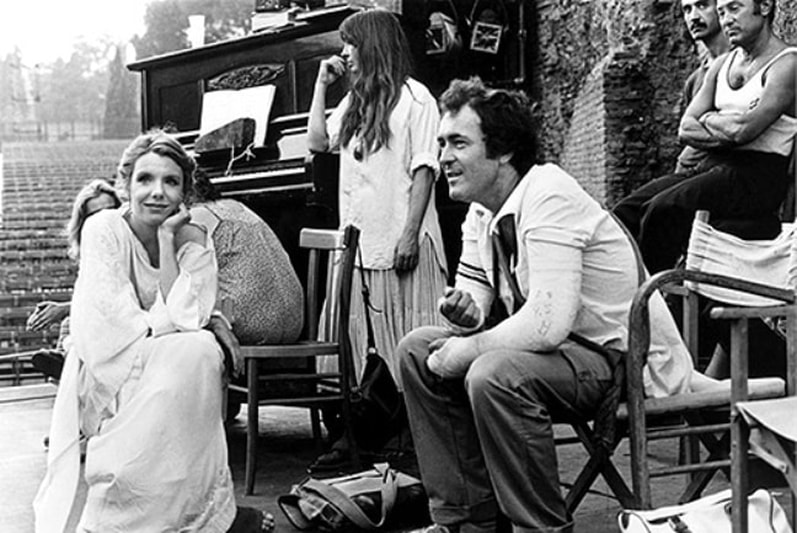

Immediately, we were transformed to the Baths of Caracalla, where the grand director was making “La Luna” in the Roman summer of 1978 – with two broken arms. There was a lot going on in a month when Romans normally head for the countryside during the annual shutdown known as “Ferragosto” – taking one major Roman Catholic holy day and turning it into a one-month holiday. Pope Paul VI had died on Aug. 6 in the summer retreat of Castel Gandolfo and the Vatican took an ungodly time getting the Pope to St. Peter’s for the funeral. I was sent there by the Times, as a learn-on-the-spot religion reporter. Pretending I knew something, I speculated on who would be the next Pope. (All wrong, of course.) https://www.nytimes.com/1978/08/07/archives/who-will-be-next-pope-cardinals-to-meet-without-clear-favorite-some.html Then the Times went on strike, leaving me in Rome with a borrowed friend’s apartment near the Piazza Navona. How sad. I sent for my wife, and we wandered the city. Right, Bertolucci. A friend of ours had a connection to another major event in Rome that summer – the making of a movie by Bernardo Bertolucci, in the Baths of Caracalla – a film called “La Luna” with a theme of incest, starring Jill Clayburgh. Our friend sent a limo to take us to Caracalla for the day, where Bertolucci was directing with casts on his arms. He had been carrying a camera, peering down into it, and had fallen off a step or a platform, and had broken both arms, but he persevered admirably. Now he bravely balanced the camera on the two casts, still framing scenes as they would appear through the lens, as directors do. A cadre of assistants hovered around him as he tottered on the steps to the stage, lest he fall again. The whole project was in his broken arms. My wife and I hung at the edge of the proceedings with our friend, whispering, perhaps even giggling a bit. Nobody seemed to mind except for Jill Clayburgh, who was gearing up for the tangled emotions of the film, wearing elegant high heels on the uneven ancient stones of Caracalla. She shot us a look or two, and we piped down. That’s all I remember, except for lurid jokes and set gossip we culled here and there. It was, of course, Rome. Matthew Barry, the young New Yorker who was playing Clayburgh’s son, had to preserve his pasty-white coloration for uniformity during the shooting, so they enticed him indoors, day after day -- no beach, no outdoor trattorias. I wondered how they kept him indoors. * * * Our friend called for the limo and a stalwart Roman driver took us toward Centro Storico. I forgot to say, it was also a dangerous time in Italy, threatened by the Red Brigade. The former Prime Minister, Aldo Moro, had been kidnapped and murdered in May and more violence was feared. “Aren’t you afraid of the Red Brigade?” I asked the driver in my minimal Italian. He tapped the solid dashboard of his limo, to signify protection of some sort, and he said, “The Red Brigade should be afraid of us.” I took his word for it. * * * Several years later, my wife was walking on Madison Ave., looking in shop windows, and she spotted the reflection of an elegant woman a few feet away, looking at her, as if to say, “Who is that?” Jill Clayburgh could not place her, and kept walking. I never saw “La Luna,” which did not get great reviews, apparently. http://theneonceiling.wixsite.com/home/pres That’s my only memory of Bertolucci – carrying on, with all the force of a great Italian director, in the August heat, in Caracalla. One of the great joys of reading the New York Times these days is the occasional and highly literate essay by Margaret Renkl, an Op-Ed contributor based in Nashville.

Renkl writes about life out there in the Real World -- if upbeat and evolving Nashville (say I, an old Nashville hand) -- can truly be called the Real World. In Monday's Times, Renkl suggests a technique for countering the discordant blares and roars and whines of -- no, she does not say that! -- the mechanical lawn-blasters who have invaded our otherwise serene lives. She talks about the garden crews that most of us employ to blow leaves around for hours at a time. (Disclosure: I recently hired a very nice crew that not only collects leaves but also seems to have produced new green grass on my ugly patch of crab-grass.) The crews in our neighborhood seem to intentionally vary their attacks so that, from March into December, there is always a group of hard-working guys whose decibel output reminds me of my freshman year at Hofstra College, when its direct neighbor across the turnpike was Mitchel Air Force, with planes warming up 100 yards away. Good for concentration on philosophy or history. To make a statement about the ugly noise in our leaves, Renkl proposes digging out prehistoric tools employed by our fellow homo sapiens back in other centuries -- an implement with a long handle and slender tines. She describes, rather lasciviously I might add, the joys of slow, careful interplay with leaves. At least, that's how I read it. In fact, it sounded like so much fun that I went out and practiced my raking, putting some leaves in bags but saving some for the little things she says inhabit the earth. I will take Renkl's word on that part; she does, after all, live out there in the Real World. (For those of us who do not have a lawn, I might suggest paring raw vegetables or cleaning a few windows. Therapy is therapy.) Try it! And look up the work of Renkl in the Times and elsewhere. She is right up there with Dan Barry and Sarah Lyall and Corey Kilgannon, whose every article I read avidly, for choice of content as well as for style. Renkl is what the great editor Gene Roberts calls, in his eastern North Carolina accent, "a rahter." And not only a rahter but a therapist. After reading her essay, I felt relaxed enough to tackle the front page. Oh, crap. * * * Here is Renkl's gem of an Op-Ed piece: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/11/opinion/red-state-liberal-leaf-blowers.html And recent works: https://www.nytimes.com/column/margaret-renkl It was mid-August of 2008. Charlie Competello had just taken his morning run in the toxic mass that passes for air in Beijing.

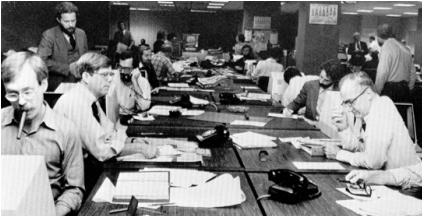

Now he was clean and dressed for business at the Olympic media center where The New York Times had rented an office for 20 people. The first thing he spotted was a forlorn-looking writer. “My laptop died,” the sad sack began. That was me. Charlie’s job was to provide technical services at big events like the Olympics and visit the bureaus all over the world, or wander around the newsroom, available to the people who write and edit the stories. He was one of us. The paper did not get done if Charlie couldn’t fix the machines and the software. This how it was when I was working. Charlie had colleagues like Walt Baranger and Pedro Rosado and Craig Hunter, who knew our jobs better than we did. (One night in Salt Lake City, after getting bad advice from on high, I was told to write something, at midnight, after the Russians fixed a figure-skating final, if you can imagine such a thing. After I stopped throwing furniture and Queens language around the room, I saw Craig standing next to me. He handed me printouts of wire stories, with all the information that would let me play catch-up ball with a midnight column. “I think this will help,” he said.) The Times had our back, with technicians who were journalists. They would find bugs in our software or frayed connections in our laptops – even schmutz clogging the keyboards. Full service. I worked with Charlie a lot -- a lean, alert guy from my home borough of Queens, who reffed basketball games in the winter, for the fun of it. We learned to rely on him the way the old Yankees would rely on Yogi Berra’s untouchable presence on a storm-tossed charter flight. Charlie was never more indispensable than in Beijing in 2008, the first Summer Games to be fully covered 24x7 on the great emerging NYT web site. We were exactly halfway around the world, which meant Michael Phelps was swimming for medals in mid-morning in Beijing but evening in New York. Any given hour, somebody needed Charlie. On that morning in Beijing, Charlie went to the basement where Lenovo had a store, and he purchased a new ThinkPad and then downloaded stuff from my busted laptop, a few hours of work while meeting all the other needs. After his run, I bet Charlie could have used a more quiet morning, but the way that job worked, there was no such thing. The Times had gone into the computer age in the mid-70’s with Howard Angione, who introduced us to the massive Harris terminals in the office. Sometimes the damn things would eat up an entire story, even if you had saved it, and we (I) would pitch a massive fit. Howard’s motto was, “If I can teach Vecsey, I can teach anybody.” And he could. For nearly four decades, I learned to rely on the Times’ techies, whatever their title was. Then I retired after 2011, and now Charlie is retiring, wisely, much younger than I was, which gives him time to relax and then find some other pursuit, or not. He’s a ref. He always makes the right call. I’m out of it now. I just hope the paper still has the backs of the people who go to wars and conventions and Olympics, fixing machines that break down at the worst possible time. * * * Speaking of valued colleagues, did you see the beautiful photo of Aretha Franklin on the front page of Friday’s paper? Her dignity and soulfulness and even her sound came through. That photo was taken by Tyrone Dukes, back in the day. Tyrone was a friend, a young brother who had served in Vietnam and was now a photographer. He could snap Aretha up close at the Apollo in 1971 and he could follow a looting rampage during the blackout of 1977. He died in 1983, at the age of 37. When I saw the credit on the photo, my eyes misted over– not for Aretha but for Tyrone. My thanks to Charlie and Tyrone and all the others, who were part of us. It all comes back to me as my colleagues prepare to cover the 2018 Winter Olympics up near the border in South Korea.

Having visited the DMZ with the U.S. soccer team in 2002, I think about hordes of crazies streaming across the border with axes in their hands. At the moment, I read there is a norovirus loose in the Olympic complex. How’d you like to get frisked by a security guard, looking a little green? There is always something. That’s why the New York Times always sends journalists who know Olympics sports but can handle anything. They have a dream team going this time – many of them colleagues from when I was covering Summer Games from Los Angeles in 1984 to Beijing in 2010, with four Winter Games included. Fear and trembling. A rebellion in South Korea brought down the government in 1987 and sportswriters were urging that the Olympics be called off. The Games were fine and I fell in love with the country. Fear and trembling. Atlanta was going to be a disaster, payback for over-reaching. There was indeed a bomb in the park one night, killing two people and injuring others – the work of one of our home-grown anti-government nutters, not foreign terrorists. It was awful. Our reporters were roused from our rooms and the editor Kathleen McElroy dispatched The Three Todds from Georgia Tech to drive us downtown in the NYT vans. Dave Anderson and Frank Litsky and others walked the street in the darkness, collecting details. And Atlanta came through the tragedy. Fear and trembling. Athens in 2004 was the first set of Games since 9/11. The fear was that terrorists were going to infiltrate Piraeus Harbor and blow up cruise ships. The worst violence was a domestic demonstration; our photo editor Brad Smith took a rock in the head and lived to tell the tale; (saw him the other day.) Juliet Macur was on the front lines and whiffed some tear gas. She’s in Pyeongchang, a columnist now. These are tough people. They don’t just keep score at games. http://www.nytimes.com/2004/08/28/world/the-reach-of-war-olympics-3-hurt-in-athens-protest-of-powell-s-visit.html (May I digress to mention the San Francisco earthquake during the 1989 World Series? We all did some instant reporting; the dogged Murray Chass reported from the pancaked Bay Bridge. http://www.nytimes.com/1989/10/19/us/california-quake-highway-collapse-desperate-struggle-for-lives-along-880.html A day later the NYT sent out a great news reporter who arrived with his boots and a helmet with a flashlight. Dude, we said, The City is making the cappuccino by candlelight.) I don’t remember any fear and trembling heading to Almost Heaven, West Nagano, for the 1998 Winter Games. Soba noodles in downtown booths. Peaceful Games. But one night I went to sleep feeling fine and came down with a raging flu. I went downstairs to the press-center infirmary to see a long line of similarly stricken colleagues. The medics put some vile-tasting grainy medicine on my tongue and said I might sleep for a day. Wonder drug. I was back on the job a day later. The Japanese took care of us. Back to the daily dose of soba noodles. So now I am retired, back home. I tend not to watch Olympics on TV because I had my fun covering them, being there. But I will be reading what Jeré Longman and John Branch and Juliet Macur and all the rest will write in the New York Times. The other day, Andrew Keh arrived (from his post in Berlin) and wrote about discovering familiar Korean comfort food in that northern outpost: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/02/sports/what-is-pyeongchang.html I’d like to think I would have written a story like that. The beat goes on.  Roy Reed, Hidin' Out. Univ of Arkansas Roy Reed, Hidin' Out. Univ of Arkansas While waiting for the Alabama results to solidify Tuesday night, I was reading the obit for Roy Reed. Roy was the great stylist when I was a rookie on the highly literate National staff of the New York Times in the early ‘70s. He could describe the exotica of New Orleans, where he was based, with the same fervor and grace he had shown in the head-breaker Deep South of the Civil Rights decade. For me, he was the correspondent to emulate. I even noticed the conservative dark-blue pinstriped suits he wore on more formal occasions, making him look like a senator. Roy Reed was from rural Arkansas and he never forgot it. I know he would have loved the campaign in Alabama – a candidate who prosecuted the murderers of little black girls vs. a candidate who stalked teen-agers in shopping malls and outside public buildings. Fortunately, the Times and other great journals have deep and talented staffs these days, to capture the ludicrous spectacle of a hustler from New York conning people out there in America. Also fortunately, I was able to hear Howell Raines, another of those great southerners who have graced the Times, talking about his beloved rural Alabama on MSNBC Tuesday night and also via a recent op-ed piece in the Times. There was a great tradition of writers on that National staff when I joined it in 1970. Gene Roberts, who had covered civil rights and Vietnam, was the national editor, expanding his staff, and he called this young baseball reporter and said, “I like the way you rot.” I sussed out that this was the charming accent of a self-styled “freckle belly” from eastern North Carolina who meant “the way you write.” Gene sold me. He and his deputy, David R. Jones, sent me off to Louisville to cover Appalachia. What a staff. Roy Reed in New Orleans. My dear friend Ben Franklin plus John Herbers and so many other good people in the Washington bureau. Jon Nordheimer and Jim Wooten in Atlanta. Paul Delaney in Chicago. B.D. Ayres in Kansas City. Jerry Flint in Detroit, John Kifner in Boston and so many others further from my region. (There was only one African-American, Delaney, and no women; the only way I can explain it is, “It was 1970.” Further down the decade, under Dave Jones, the NYT added Grace Lichtenstein in Denver as the first female national correspondent and later Molly Ivins, Judith Cummings, E.R. Shipp and Isabel Wilkerson, who would win a Pulitzer under Soma Golden's editorship.) In my years, a kind day editor, Irv Horowitz, in New York, kept track of us, and great copy editors had the time and mandate to ask you to rewrite something so it would read better. We communicated by telephone – not email and not cell phones. Such a primitive era. I relied on these older professionals to teach me something, anything, by osmosis. I would like to correct one statement in that obit concerning Roy Reed: It said he was down the road getting a soft drink when James Meredith was shot on his epic protest walk through Mississippi in 1966, and that Roy’s respectful colleagues later presented him with a Coke bottle trophy that said “WHERE’S ROY REED?” in memory of his brief absence. The fact is, there was another day when Roy turned up missing. Dave Jones, our ringmaster in New York, was trying to find someone to get to a story in the South that seemed urgent at the time. (I can no longer remember what it was.) Dave tried me in Louisville. No answer. Dave tried one of the Atlanta guys. No answer. Dave tried Roy Reed in New Orleans. No answer. Ever diligent, Dave solved the problem some other way, and the world went on. A few days later, the mystery was solved. A delightful March zephyr had moved north from the Gulf into Louisiana, into Georgia, and even to the southern banks of the Ohio River in Kentucky. All three correspondents had been, shall we say, indisposed. On the phone, I asked Roy where he had been when the office was looking for us. In his Arkansas drawl, Roy said: “Hidin’ out.” I adopted his phrase for times when I was unfindable. Bless the era before cell phones. Bless the southern phrases, the southern outlook, I learned to understand from my colleagues, better reporters than I ever would be. And bless Roy Reed, for writing about a region that continues to produce great stories, from the new generation. ------------------------------------------------------- Nina Simone was voted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame this week. She passed in 2003; what took them so long? Not sure what Simone would have thought about that, but she surely would have loved the vote in Alabama Tuesday night. A candidate who was receptive to the integration of his high school back in the day beat out a religion-spouting accused pedophile who thinks slavery came during a good time for families in America. Simone knew it all, put it into her music. She was an American treasure. She mentions Alabama way up high in her signature song, “Mississippi Goddam.” Ladies and gentlemen, Miss Nina Simone: On his theory that it is not every day that a person turns 90, Frank Litsky threw himself a party the other night.

Frank drew over 40 old hands from the Times, who celebrated him – and our business, which was putting out the paper on deadline. Looking great, sounding great, Frank noted others in his nonagenarian state – Tony Bennett, Fidel Castro, Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Cloris Leachman, Jerry Lewis, Mel Brooks, Don Rickles, just to name a few. (The overall list is impressive.) Colleagues from the 50’s and 60’s, Gay Talese and Bob Lipsyte, made lovely talks about Frank’s energy and knowledge and productivity. In an informal chat, I reminded Frank of my nickname for him -- Four-Fifty. This stems from when I came over from Newsday in 1968 with a lot to say, and Frank was the day assignment editor who shoehorned stories into the section. I would check in each day with proposals for lengthy rambles about the Amazing Mets or the post-Mantle Yankees, and Frank would cut me dead with the fatal words: “Four-fifty.” That is, 450 words Frank Litsky stifled my imagination and made it impossible to show my stuff, to the point that my career and the paper suffered terribly. He has never repented. We crowded into Coogan’s Restaurant in Washington Heights, near the armory which has been refurbished to house Frank’s beloved track and field. (The proprietor, Peter Walsh, himself a copy boy at the Times in the late ‘60’s, even serenaded us with a song in Gaelic.) We all had histories with each other, over the decades: Sports editors who had made tough decisions. Copy editors who had pulled stories together minutes before the press run. Reporters who had broken good stories. Columnists who had typed our precious little thoughts. Clerks and office managers who made the whole thing work. Margaret Roach, the journalist daughter of James Roach, the beloved sports editor of the ’60’s, was there. Joe Vecchione and Neil Amdur, two subsequent sports editors. Fern Turkowitz and now TerriAnn Glynn, who held the section together. All of us could, if we tried, recall snit fits and frustrations with some of the people we were now hugging. But what we remembered most was somehow letting the esteemed production people push the button on time. What we had in common was the identification with the physical product that people held in their hands, read seriously. It is in our blood. Frank Litsky, who covered Olympics and pro football and women’s basketball, has known good times and terrible times, and now he sat there, a wise old Buddha figure with a New York accent, with “the love of my life,” Zina Greene, listening to old stories, some true. One thing I learned that night was that in his alleged retirement, Frank has contributed over 100 obituaries of sports figures, sitting there in the digital can. I am betting all his masterpieces go over 450 words. Just saying. The great journalist Sydney Schanberg died the other day at 82.

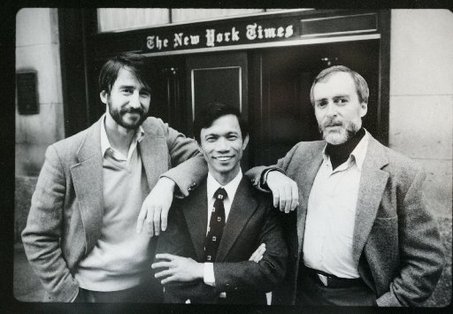

(Please see the lovely tribute by Charlie Kaiser, another ex-Times person:) www.vanityfair.com/news/2016/07/the-death-and-life-of-sydney-schanberg I was more of an admirer than a close friend, but we had one moment of contact that I probably recalled better than he did. This was on the spring day in 1976 when he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize after having stayed behind in Cambodia to write about the ravages of a society gone mad. He had become separated from his colleague, his friend, his brother, Dith Pran, who was still missing. I knew Schanberg only as a presence who moved through the city room now and then when he was on home leave. Foreign correspondents have an aura. I knew I could not do what they do, and I admired them greatly. On Pulitzer day, I was a cityside reporter, covering the suburbs, but if the city editor spotted you walking and breathing you could get sent anywhere – a shootout in Brooklyn, an assassination in Bermuda, a visiting king or prime minister in our town. One editor asked me to interview Schanberg for the profile of him in the paper the next day. He was surrounded by friends and I introduced myself and we walked to a less noisy corner and I started with a very general question. This gutsy correspondent who had survived the Khmer Rouge began to cry, and then he began to sob. I did what reporters should do. I went silent and waited for him to make the next move. He was a pro. He gathered himself and managed to say a few things: “I accept this award on behalf of myself and my Cambodian colleague, Dith Pran, who had a great commitment to cover this story and stayed to cover it and is a great journalist.” Schanberg told me he had spent the last year “in a state of deep decompression – I lost a lot of friends over there.” I knew enough not to go much further. I typed up his words, which were in the paper the next day. * * * In 1979, Schanberg’s friend, his brother, made it over the Thai border and soon became a photographer for the Times, a sweet and slight man who made us happy just by being alive. The two buddies got to watch Sam Waterston and Dr Haing S. Ngor portray them in the movie, “The Killing Fields.” (Dith Pran died in 2008.) * * * Sydney was appointed Metro editor in 1977 shortly after I had taken a new post reporting on religion. The Times already had an expert on theology and religious history, and Sydney did not think they needed a second reporter on such a soft beat. He said he would find something else for me. I was enjoying the beat – Hasids one day, nuns the next day, Evangelicals the day after that. I did not want to get shifted. A few days later I just happened to be having lunch with the rabbi who was the spokesman for the Orthodox wing of Judaism in North America. I allowed as how I was feeling a bit glum that day because they were cutting back on the religion beat. My rabbi thought that was too bad because the Orthodox liked the way I, a Christian, wrote about them. It took me 10 minutes to walk from Lou G. Siegel’s on W. 38th St. to the old Times building on W, 43rd St. When I reached the newsroom, Sydney spotted me, and with a mixture of annoyance and possibly admiration he said, “Aw, fuck it, you’re staying on the beat.” I asked no questions but I assumed my rabbi had called a higher-up (not that Higher-Up) and arranged things while I was walking five blocks on Seventh Ave. Sydney held no grudges. He played hardball; he understood it. The next spring, he called me to his desk and said Passover was starting that night and could I get him a Haggadah, the guide to the rituals of the Seder. “Pretty contemporary,” he said. “But not too liberal. You know.” Oh, that Haggadah. I took the No. 1 train uptown to a Judaica bookstore, rounded up a few Haggadahs, and presented them to Sydney. I never asked how the Seder went. He was a hard editor to work for because, like most great reporters, he was used to cutting his own deals; after all, he had defied his own editors by not leaving Cambodia. He was not so good on leadership, on listening to his staff, but he was smart and tough and talented, and I admired him greatly. Later he wrote a column and inevitably butted heads with his own editors, and left the Times. Over the years we met at Times get-togethers and funerals, and we got along fine, old colleagues who had been through stuff together -- but not the kind of stuff he had seen in Cambodia. Every time I saw him, I thought of him crying in the City Room for his missing buddy. (Above: Bud Collins Interviews Muhammad Ali, 1968.) When the Times called and asked me to write something about Ali, I stuck close to the theme of personal fleeting encounters with Ali – once upon a time in America.

There was no time or space for two other impressions of Ali, so I am getting to them here, both from 1996. The Anniversary. In March of 1996, I drove down to North Philadelphia to Joe Frazier’s gym, to talk about the 25th anniversary of their first fight in 1971. I knew Ali could no longer discuss that fight, but Smokin’ Joe could. I found him smoldering, resentful over the way Ali had pulled racial attitudes on him, calling him a gorilla and mocking the way he spoke. "I won that fight," Frazier said about 1971. "Guess I won the other two, also. I'm here talking to you, right?" He was crowing about still being able to work out and drive a car and talk to me, quite intelligently, his speech slightly difficult to follow because he grew up in a coastal region of South Carolina where the African dialect of Gullah was an influence. I could understand Smokin’ Joe just fine. He felt that Ali – sometimes he called him “Clay,” his birth or slave name – was duplicitous, manipulative, vicious. Two of Frazier’s children were at the gym – Marvis, preacher/boxer/companion, and Jackie Frazier-Lyde, his athlete daughter, now a municipal judge. Both were a tribute to Joe, and to their mother, adults with brains and compassion. They told him, Dad, you have to get over it. I knew Joe and Marvis to be good people. They had recently driven from Philly to Long Island in a major January snowstorm to attend the funeral of a dear friend, arriving at the synagogue after the service and staying a long time. I felt for Smokin’ Joe, who passed in 2011. In the mirror of time, Ali was diminished by his treatment of Frazier. http://www.nytimes.com/1996/03/03/sports/perspective-boxing-25-years-haven-t-softened-blows-frazier-finally-earned.html?pagewanted=all The Olympic Torch. A bunch of reporters were sitting in the press tribune at the Olympic Stadium, speculating on who would have the honor of carrying the torch on its final segment – a famous athlete? A King or a Carter? An artistic symbol of the new South? I don’t think any of us were prepared for the slow, deliberate trudge of the figure in white, one hand quivering, one hand carrying the torch up a narrow pathway. When we realized who it was, we gasped and then we did something banned in press boxes – we stood and exchanged high fives. Muhammad Ali. Perfect. Everybody understood the forces within that diminished figure – the draft, the conversion, the hyperbole, the beauty, the fights, the path from alien radical to stricken native son. That happened on a Friday night, too late for the Saturday paper. A few hours later for the Sunday paper I wrote this short, personal, emotional tribute less to Ali himself than to the Atlanta organizers who, perhaps to my shock, totally got it. (With a major nudge from Dick Ebersol of NBC.) http://www.nytimes.com/packages/html/sports/year_in_sports/07.19.html * * * (Finally, my thanks to so many people who have responded to my column in the Times. My praises to the professionals who produced and distributed the Ali tribute in about 170,000 copies of the final edition of the Saturday paper – including one on my doorstep.) There is only one way to ponder family genealogy -- with humility, knowing that others do not know their distant past.

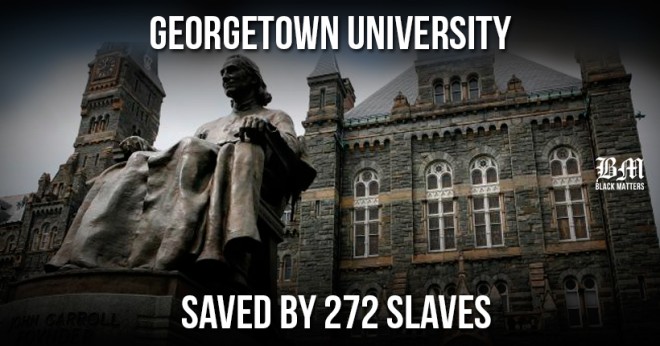

That lesson is brought home in Saturday’s New York Times, with its touching article on descendants of 272 slaves who were sold by Georgetown University in 1838 to keep that school solvent. In the article, four people in Louisiana talk about the trail of slavery with the grace of survivors, through strong families as well as the influence of the very same Catholic Church that sold them in 1838. In no small way, religion seems to have helped them, given them strength. That is the paradox. Their words, their wisdom, are a lesson to many people, including me and my wife, who can trace parts of our families back for centuries. We often feel humility toward in-laws and friends descended from Africa, as well as our Jewish friends who listen with kindness and curiosity when my wife talks about her genealogy research. We know of the gaps and absences in many lives. I can relate to some small degree because my father was adopted by a Hungarian family, his birth records sealed and apparently later destroyed by a fire in New York City. We only know his name when he was placed in an orphanage. I have always assumed he was part Jewish. I can live with that mystery, knowing of my mother’s maternal side back to County Waterford in Ireland (hence my treasured Irish passport.) My mom’s Belgian-Irish cousins were heroes in Brussels during the War.) My mother’s paternal side, Spencer, goes back to Leicestershire and later to Australia and back to England again before immigrating to the U. S. My wife has been digging into her roots in England, with help at the Mormon center in London, and lately she has been going on line into village records, as well as an ancestry web site. Over the years she has also taken information from relatives, including her grandfather, before he passed, and to this day from aunts and uncles still going into their 90’s. (Childhood farm living, no smoking, no drinking, equals longevity.) Her grandmother’s side comes through a branch of English Whipples who came into Rhode Island around 1632 and moved down to Ledyard, Conn., mingling with people named Rogers and Crouch and Watrous, many buried in the Quakertown cemetery. Her grandfather’s side traces to around Rochdale, Lancashire, in the 16th Century, with names like Grundy and Clegg and Schofield and Heywood. My wife – who spells her name Marianne – notes that many of our English ancestors had the same names – Mary Ann, Sarah, Elizabeth, Edith, George, Frederick, Arthur and John, a million Johns on my wife’s side. Sometimes she says we could be related. Aren’t we all? We have inherited little, except names and genes and mystery, along with a sense of being part of something. My wife – who loves India deeply; has been there 13 or 14 times – was told by her grandfather that a female ancestor, Sarah Schofield, had ridden an elephant in India while her husband was posted there by the colonial army in the 19th Century. She feels kinship over two centuries. None of this means much, except a sense of heritage. My wife’s people could make things with their hands; they were church-goers, people of peace, some of them abolitionists. She is still ripping mad that Spielberg’s movie, “Lincoln,” showed a Connecticut senator voting for slavery. History becomes personal all over again when we read the article by Rachel L. Swarns and Sona Patel in the Times about the good people of Louisiana, who want some tangible memorial to the 272 ancestors who were sold by a college. As we read the quotes in the Times, we feel sadness that others do not have the same reassurance of ancestors, of place, of choice, of freedom. What a wonderful night for journalism, at the end of the Academy Awards, to see “Spotlight” honored as best picture. The film shows how the Boston Globe pursued a history of abuse by priests in the region.

Yes, journalism is still being practiced at some of the surviving journals in the United States, the ones that devote precious time and money and staff to finding stuff out, and publishing it. However, my pride in colleagues is tempered by the realization that not enough people read the information – and opinion – in the surviving fringe of American journalism. I occasionally talk at colleges and high schools and generally get blank looks from students when I ask how many people read newspapers. Even on line? I ask. Some nod yes, but cannot give examples. They like things that jump around. But apparently so do their elders. A frightening swath of Americans seem to think Donald Trump knows how the world works. Because people do not read newspapers, in print or on line, they do not know that he is generally regarded with a shrug and a smile in New York, the town that knows him best. Oh, that guy. This reality was brought home recently by two articles in The New York Times about Trump’s reputation (marginal) in New York real estate circles, and how he bled investors in a golf resort in Florida. This is who the guy is; this is how he operates. But unless people delve into the details – that is to say, read – they will never know. This is where we are going. Here are two stories most of America will never read: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/24/nyregion/donald-trump-nyc.html?_r=0 http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/27/sports/golf/at-trump-club-in-florida-some-members-want-their-money-back.html Now Trump is threatening to suppress newspapers when he becomes President. Perhaps he will send his Brown Shirts to crowbar the printing presses. Here’s another look at Trump, from 1990, by Marie Brenner in Vanity Fair -- the attention-deficit playboy-builder we knew before he unleashed his public bully. http://www.vanityfair.com/magazine/2015/07/donald-ivana-trump-divorce-prenup-marie-brenner I also recommend two current articles on Hillary Clinton and Libya, stemming from what is obviously weeks of work: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/28/us/politics/hillary-clinton-libya.html http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/28/us/politics/libya-isis-hillary-clinton.html One last thing about journalism: Margaret Sullivan is leaving her post as public editor at the Times to become a media columnist at the Washington Post. In my now-outsider’s opinion, I wish the Times had found a new gig for Sullivan, the best public editor the Times has had. I hope these links work in your system. If not, the stories are easily looked up. As a proud alumnus, I am glad the Times values its work by charging for it on line. It costs a lot of money for the Times and Globe to cast their spotlight. The Mets opened their series in Los Angeles Friday night and beat one of the best pitchers in baseball, Clayton Kershaw, with David Wright earning a 12-pitch walk in the first and then driving in two vital runs in the seventh. But you already know that.

(The Mets then got upended, in more ways than one, Saturday night. Plenty of opinions on that slide by Utley. See Comments below, and please add your own. But first, let's talk about the "paper" that made deadline two straight evenings with crazy stuff from LA.) The other team that had a great night on Friday was New York Times, which delivered 115,000 copies of the paper, the version you can hold in one hand while eating a bagel with the other hand. That paper was in my driveway in a nearby suburb at 7:30 AM – not bad for a game that ended after midnight. Tim Rohan, out in Los Angeles, completed his very readable article in a hurry and sent it to my friends in the Sports Department, who shaped it and sent it to the plant in College Point, Queens, where people were waiting for it. We got it at 1:15. On presses at 1:26. Overall, 98% on time, one late NJ truck by 3 mins. That was my note from one of my friends in the handsome plant alongside the Whitestone Expressway. The Times is doing quite well with its print edition, as other papers basically give up. The coup on Friday night/Saturday morning reminds me of a similar night, Oct. 14-15, 1992, when Francisco Cabrera, an obscure Atlanta Brave, delivered the hit that won the National League pennant (and broke the hearts of a Pirate team about to be atomized by free agency.) In the midnight hour, I found Cabrera in the melee on the field and rushed upstairs to write a column with a headline: His Name Is Francisco Cabrera. A few hours later, I caught the first thing smoking, and was back in my driveway before noon. The paper was waiting for me. The column was in print. I love the Web. I’m poking around on it all day. It’s the future. The Times does spectacular things on line. I also love print. Look at the front page of the Sports Section Saturday – huge picture of Jacob deGrom, locks flopping, fastball flying, story by Tim Rohan, and below that two more excellent articles by esteemed colleagues -- Chicharito of Mexico by the Europe-based Sam Borden and the wretched sightlines at the hockey opener at the Barclays Center by Filip Bondy, recently departed from the fading Daily News, now doing the occasional piece for the Times. The Mets would come back out and play again Saturday night. So would the Times. As one of my great bosses, Joe Vecchione, said a few minutes after the Times revamped in minutes on Mookie Night in 1986: “We do it every day, Kid.” This is a great time of the year in the United States. The final four of Champions League soccer is being piped in during mid-afternoon across this huge country.

On Wednesday Americans got to see Messi break down Bayern Munich with two killer strikes, three minutes apart, as Barcelona won, 3-0, at home in the Pep Guardiola Bowl – his current team (Bayern) against his old team (Barça). On Tuesday, Juventus held off Real Madrid, 2-1, at home, as described so well by Sam Borden in the Times. I enjoyed watching old hands like Buffon, Pirlo and Chiellini, who sported a bandage and a bloody jersey -- and Suarez was nowhere in sight. (Euro calcio scribes dispatch with first names; everybody knows the players, or is supposed to. Fact is, American tifosi recognize the manic features of Buffon, who has been a staple of our lives for two decades. We know this stuff.) Next week the teams play again and the final is June 6 in Berlin. Pubs and restaurants will be jumping in New York as fans celebrate the true rite of spring. The big question is: how far can the growing sophistication and demand for soccer go in the New World? We do know that European clubs are thrilled to make money here. In July the master impresario Charlie Stillitano will import some of the best squads for the International Champions Cup -- what amounts to pre-season training. (That’s right; these blokes will be whacking away in two months.) But how long will American fans, with their discretionary income, be willing to serve as out-of-town tryout audiences, like spring training baseball fans in Florida and Arizona, or theatre-goers watching plays before they reach Broadway? Americans are getting the hang of world soccer. The New York Times dispatched Sam Borden to Europe to add to what Chris Clarey and Rob Hughes have been doing. Americans know all about master schnorrer Sepp Blatter of FIFA. (Check out Bloomberg’s big piece on Blatter.) Every four years, American fans must settle for their plucky Last Picture Show national squad. Major League Soccer is growing its product correctly. I think the time zones over the Atlantic are a barrier to having a Boston team or a New York team playing in a top European league. But money can make anything happen, I suppose. It’s been a huge transition in the past generation, just having the top clubs show up in our summer. In 2001, Bayern won the Champions League on a Wednesday night in Milan and flew home for a parade in Munich on Thursday and celebrated with no sleep until the flight to Newark on Friday for a Saturday night exhibition. Bayern scraped together eight starters from the final but their legs and brains were shot by the time they wobbled onto the field in New Jersey. The hideous MetroStars won the exhibition, 2-0 – and over 30,000 fans showed just to watch the best players in the world, hung over. More recently, Bayern has opened a New York office. You think they’re not serious? I knew the appetite for American money was growing when Sir Alex Ferguson deigned to lunch with American soccer writers before a rake-in-the-bucks swing in 2003. The extroverted Dutch striker Rood Van Nistelrooy told a charming story about getting into a coed pickup match in North Carolina the summer before and finally being recognized by a female opponent. Footy in the Colonies! In 2011 I covered a Liverpool-AC Milan match in hallowed Fenway Park. And I used to watch Champions League matches in BXL, Foley’s, and the late, lamented L’Angolo in Greenwich Village. We Americans have learned a bit in recent decades. But will we ever really be part of world football? Or will we remain well-heeled consumers rather than participants? Your thoughts? The Times put David Carr on the front page, above the fold, as well they should.

He gave everything he had until he collapsed in the office Thursday evening and passed at 58. He was a voice, an honest voice, a reliable voice, a smart voice. I never met him – that happens at such a large paper – but I read him, and I knew about him, his long addiction, his rehabs, which only made me respect what he accomplished even more, but mostly I knew him through the digging he did and the insights he provided. He was burning it in recent days -- my wife said he looked like hell on the tube early Thursday -- explaining all the breaking media news. I can only guess at the high-wire act to write, edit and print the obituary on the front page, in literally minutes, before the first edition of “the paper.That tangible part of journalism still matters in these digital times, as David Carr noted so well. * * * With homage to that great pro, I’d like to drop a few other current thoughts on the media: *- I have never totally trusted the concept of the anchor, those great men and occasional women, who spoon-feed us the news on television. I grew up on Edward R, Murrow and his CBS colleagues at the end of the war. They were reporters; today’s anchors are performers. I always thought Brian Williams was a symptom of the time -- show biz. I’ve often wondered when anchors are preening in front of the camera how they managed to do any reporting. *- Bob Simon of CBS was the real deal, a correspondent who went to all those places, with a staff, of course, but also with reporter smarts. When he reported on 60 Minutes, you knew he had done the homework. His death in an auto crash brought out a very impressive detail: he had just worked on a piece on Ebola medicine, at the age of 73. *- I’ve always been leery of the Jon Stewart-Stephen Colbert school. They are funny, but perhaps without meaning to they have insinuated themselves ahead of reality. For the new generation that does not read newspapers, they are the first line of information. Kids hear about vital events from a very savvy adult making yuks on the tube. Not Stewart’s fault. Our fault. Stewart’s remark to Brian Williams’ face is classic: “You don’t write any of that stuff,” Stewart told Williams, as David Carr reported on his final day. “They take you out of the vegetable crisper five minutes before the show and they put you in front of something that is spelled out phonetically. I know how this goes.” *-And finally, I have no problem with President Obama’s video for BuzzFeed, to promote the program bringing health care to more people. (How dare he!) We all know Obama is a writer and a performer and a wannabe hoopster. He made me and my wife – who predicted his victory in 2007 – roar with his delivery in the BuzzFeed video. Some people may fret that the President demeans the office. (That is Boehner's and McConnell's job.) I say, let the man have a few minutes of fun. As I sit here typing my little therapy blog – not in classic blogger underwear, I promise – I am supervised by a phalanx of editors.

They perch over my shoulder, the ghosts of deadlines past, monitoring my every whimsy. Before I can push the “Submit” button on my site, I must satisfy editors who kept me tethered for all those decades. They suggest temperate phrases like “alleged” and “so-called” and “was said to be” for assertions I cannot totally back up. “You need to do this over,” I can hear Jack Mann or Bob Waters snarling at me in Marine patois when I was learning to play the game right at Newsday. “Ummm, that doesn’t read like Vecsey,” I can still hear a Times national-desk editor named Tom Wark saying to me about a long profile of a bank robber who had earned a degree behind thick federal walls. “Could you run it through the typewriter again?” What a wonderful compliment. “Ummm, could you make a few more phone calls?” I can hear Metro copy-fixers like Marv Siegel and Dan Blum, or Bill Brink in Sports, saving me more than once. And early on Saturday mornings, right on deadline for my Sunday column, I would get a careful final read from the superb Patty LaDuca (about to retire, for goodness’ sakes.) When I am talking to journalism students, one of my main points is that if you have an editor supervising your work, you are actually participating in journalism. But if you expect your precious words to appear in print just the way you wrote them, you are merely a blogger. Editors keep you from making an ass of yourself. And sometimes the best editor is….yourself. I was thinking about editors a month or two ago when a major movie studio allowed “The Interview” to come out with the premise of the dictator of North Korea having his head blown off. Charming. The self-indulgent director waved the “creative freedom” flag, and the studio heads folded, with predictable world-wide tremors. Movie directors and producers could use a reality check from an editor – “Ummm, could you look that up?” -- when making films like “Selma” and “Lincoln,” as Maureen Dowd pointed out on Sunday. More recently, a weekly satire magazine in France published a cartoon of the Prophet Muhammad, touching off horrible violence around the world – violence that surely had been waiting to be fomented by opportunistic lunatics. Then the staff came back with another cartoon of the prophet. Was any of that necessary? Journalists have this implanted in their brains at an early age, by editors. What are the consequences? What does the other side say? Those of us who learned to present all sides – to make a few more phone calls – are lucky. So are the people who read (or watch, or listen to) those increasingly rare sources. (I don't count Stewart or Colbert. I am talking about their sources. That is, journalists.) * * * One of the most rational posts on the Charlie Hebdo issue is by Omid Safi, the director of Duke University's Islamic Studies Center, for that great site, onbeing.org. http://onbeing.org/blog/9-points-to-ponder-on-the-paris-shooting-and-charlie-hebdo/7193 And here are a few others: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/10/arts/an-attack-chills-satirists-and-prompts-debate.html?_r=0 http://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/unmournable-bodies http://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/charlie-hebdo-shooting In admirable journalistic precision, it did not take Sam Roberts long to get to the point about Arthur Gelb.

“Sheer force of personality.” Words 5 through 8. Gelb was a whirlwind, make you crazy, make you work better. He was our boss, our captor, our rabbi, and now he is gone at 90. So soon? If anybody wants to know about The New York Times – why one passionate sliver of society is paying so much attention to the current changes – it is all contained in Arthur Gelb’s obituary in today’s paper. He personified the power and the glory, the curiosity and the authority, of the Times. Just read Sam’s obit. But let me say a few personal words. I went to work for him on Jan. 2, 1973, after choosing to come back from a great job in Appalachia. Needed to get home. I was taken in by the Metro editor, long and twitchy, whom I did not know but would soon come to think of as a stork on speed. Arthur had a zillion ideas, half a dozen of which were brilliant, and he was capable of great enthusiasms and innate wisdom. “Cover Long Island like a national assignment, the way you did Appalachia,” he told me. He got it. Whenever other editors tried to change my direction, I would quote him. He loved to hear about things outside his urban experience. People fish for snappers and bluefish less than an hour from Times Square? How long has this been going on? Get photos! Write long! We’ll put it on the second front! Every day he promised 10 or 12 reporters that their literary efforts would be on the second front. The next day, from the obscurity of B17, most of the reporters wanted to throttle him. He was sometimes kind, liked to reward people, in a job that necessitated hard decisions, in a newsroom stocked with talent (and still is.) Sensational new recruits got heavy play. One year it was the wonderful Anna Quindlen. The next year it was the marvelous Alan Richman. “There goes Alan Richman,” Quindlen once quipped, but nicely. “He’s the new Anna Quindlen.” She did all right. So did Richman. So did a lot of Arthur’s people. There was one way to get through to him. I tried acting disturbed, but how would anybody tell in that setting? Grace Lichtenstein, one of our hardiest reporters, who could go anywhere, do anything, found a way to get through to Arthur. She would complain to him in the center of the newsroom – until tears started welling in her eyes. “Don’t cry! Don’t cry!” he would plea, hustling her into a conference room. She did fine. He was a big softy, under that manipulative armor. (THIS JUST IN: Check Grace's letter in the NYT Thursday:) http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/22/opinion/arthur-gelb-of-the-times-a-maestro-in-the-newsroom.html?partner=rssnyt&emc=rss&_r=0 (GREAT MINDS THINK ALIKE; WE HAVEN'T COMPARED NOTES IN A FEW YEARS. GV.) He took care of his people. I had somebody who knew me, as long as he was in the building. It was a comforting thought. When he retired from the news operation, there was a gathering of his people, hundreds of reporters and editors who had suffered and thrived under him. Charlayne Hunter-Gault was the lead speaker, telling stories of the mythical second frontings, the weird assignments, the dead ends, the forgotten promises. In the front row, the old rascal sat there, a huge smile on his face, surrounded by his people. Yes, his smile said, I did all that. Just read Sam Roberts’ piece: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/21/business/media/new-york-times-editor-arthur-gelb-dies.html?_r=0 And read Pranay Gupte's piece, too. Pranay was there. http://www.livemint.com/Consumer/zgQ0MGi2WcIK9ddZDXXoIP/Arthur-Gelb-creative-tower-of-tension-of-The-New-York-Time.html I’ve never done much volunteer work because I was always busy.

Plus, my theory was, I was more valuable pecking away at the laptop for dollars than getting in somebody’s way. However, I have been in awe of a couple of new-generation doctors I know who volunteer in places like Haiti and Africa. And I saw my wife make a difference as a volunteer an orphanage in India. Having more time these days, I signed up for a few hours of labor with some new friends from The New York Times plant in College Point, Queens. Ever since the production and delivery part of the paper moved out of W. 43 St. in 1997, I have missed the bustle of the trucks and the workers on the sidewalks and elevators and in the cafeteria. Last week, Mike Connors, managing director of the Production Department, invited me to help pack food at the City Harvest warehouse right off the East River in Long Island City, Queens. Over 30 volunteers were given gloves and divided ourselves into two groups. One prepared bags of donated non-perishable food – bottled water, coconut water, canned tuna, dry cereal, beef jerky, packaged chocolate chip cookies, sardines, granola bars, tomato soup, beans, crushed tomatoes, pasta and anchovies. Anchovies! I was advised by Ernie Booth, an executive at the Times plant, that my vast skills were urgently needed at the other job – shuttling oranges from refrigerator-sized cardboard boxes into bags that held 15-20 oranges, large and small. I realized right away how much I enjoyed the teamwork – how individuals made room for each other, how they solved problems like getting oranges out of the bottom of the crates (tipping them and getting down on our knees, scooping with our forearms.) Later I tried bagging the oranges, chatting with new friends like Deirdre Deignan, an official from the Times plant, and Andy Gutterman, the executive director from HR/Human Relations, and other volunteers, about sports and past jobs. We worked at a fairly intense pace, with a sense of purpose. By late afternoon, most people had to go back to produce and deliver the next day’s Times. The City Harvest supervisors read off our output – 10,000 pounds of dry food, 7,000 pounds of oranges, eight and a half tons of food for dozens of eligible New York families with incomes under $60,000. week later, I look forward to spring when the NYT will do it again. I urge anybody not to wait as long as I did to volunteer a few hours, somewhere. For information, please see: http://www.cityharvest.org/ |

Categories

All

|