Cate Ludlam in Prospect Cemetery, Jamaica, Queens Cate Ludlam in Prospect Cemetery, Jamaica, Queens Before the summer totally gets away, I need to write about one of my loveliest outings of recent months – a visit to a historic cemetery I had not known existed. I went with a few history-minded friends from Jamaica High School, who are forever bonded to central Queens, where we were raised. The region goes back to Dutch and English settlers in the 17th Century, and, of course, the Jameco tribe of Native Americans, who named themselves after the Algonquin word for beavers, who were here first. We acquired our educations and lifelong friends at Jamaica High without ever knowing about Prospect Cemetery, on Beaver Road, now surrounded by York College in South Jamaica. The private cemetery is one of the oldest in New York City for English settlers. Our tour was conducted by Catherine Ludlam, who is related to other old Long Island families; (the name is sometimes spelled "Ludlum," but the original, from Matlock, Derby, England, is spelled "Ludlam.") Either way, Ludlam, a retired computer consultant, has helped revive the cemetery from the neglect and vandalism over the decades. How did old Jamaica types, now scattered in our worldwide diaspora, hear about Prospect Cemetery? The credit goes to my good friend Michael Schwab, who went to Jamaica half a decade later than I did, and is now a retired judge from the apple-and-cherry paradise of Yakima, Wash., living in Seattle. Michael and I became pals through his veneration of Joe Austin, the grand mentor to generations of basketball and baseball players at the St. Monica’s Parish. (Michael is as Jewish as the prune danish he craves on his regular homecomings to Queens.) Michael and his lovely wife Jane, of blessed memory, would seek out historic spots on visits to Queens. Across the street from where St. Monica’s (with its basement basketball court, where a player named Cuomo practiced running his defender into murderous tile pillars at center court) used to be, is the historic cemetery. Who knew? Michael Schwab became a fan of the cemetery, via Cate Ludlam, and asked me to round up a small group of Jamaica pals when he was in Queens a few weeks ago. So I rounded up history buffs -- West Side Shelley and East Side Jean and Trumpland Michael and Westchester Wally and my wife, the non-Jamaican. Cate took us first to a family chapel, built for three Ludlam sisters. During the lawless 60s and 70s, vandals delighted in shooting out the stained-glass windows, now replaced since the site was secured by the growth of York College. Next, we walked through thick grass (Eco-Lawn, a brand that needs no mowing) and Cate pointed out tombstones that told of life from one generation to the next -- no historical footnotes or explanations, just names and dates. The earliest recognizable tombstone was: for Mary Fitch: (“Died: Jan. -- (?) 1709. Age 17 years.”) Nearby in the Hariman family section was the tombstone for “Jane Lyons, a colored woman, who upwards of 65 years was a faithful and devoted domestic in the family of James Hariman, Sr. of this village, died Dec. 19, 1858. Age 75 years.” And not far away was the tombstone for James Henry Hackett, a noted Shakespearean actor who in 1863 impressed a resident of Washington, D.C., who wrote a fan letter signed “A. Lincoln.” As we trekked around the cemetery, Cate told us about her earlier explorations – the homeless man, living in the underbrush, who shocked her, and the student dig for obscured markers that ended prematurely with the discovery of the skeleton of a child – identity and cause of death, unknown. Cate mentioned the sad discovery to a relative, a writer named Cornelia Read, who subsequently included Cate in a novel called “Invisible Boy.” Nearby, we saw the weathered tombstone of Increase Carpenter -- a stunning flashback for me to the late 40s, when my class at P.S. 35 in Hollis used to take a walk to the site of the farm of Increase Carpenter, the quartermaster in the upstart militia. This farm was where Gen. Nathaniel Woodhull was captured while ferrying cattle eastward to keep them out of the hands of the British. When Woodhull refused to say "God save the king," a British soldier whacked him in the arm with a sword, and the general died of the wound. Cate Ludlam knows the details. She is a member of the Increase Carpenter chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. My friends are proud of our roots in a landmark public school. (The city, in all its wisdom, lost control of the school and terminated it a few years back.) In our ways, we luxuriated in being in downtown Jamaica, where the el used to run, where Gertz used to be, just south of the main line of the Long Island Rail Road, still rumbling. After the tour, we repaired to a terrific Portuguese restaurant -- A Churrasqueira -- a block from the modernized Jamaica station -- a perfect ending to the day. * * * I have barely touched the surface of Prospect Cemetery. For further information, here are a few links: Donations to maintain the cemetery may be made to: PCA ℅ Cate Ludlam, PO Box 553, Oyster Bay, NY 11771 http://www.prospectcemeteryassociation.org/ http://www.nylandmarks.org/about_us/greatest_accomplishments/prospect_cemetery/ http://www.nylandmarks.org/programs_services/loans/historic_properties_fund/projects/prospect_cemetery_revitalization_initiative http://forgotten-ny.com/2004/03/forgotten-tour-15-jamaicas-prospect-cemetery-and-king-mansion-queens/ http://www.nytimes.com/2004/03/22/nyregion/at-a-legendary-cemetery-a-rare-look-behind-the-gates.html?_r=0 http://longislandgenealogy.com/PROSPECT%20CEMETERY.pdf As we write post-mortems of this failed presidency, may I ask a favor of everybody, including media people I admire?

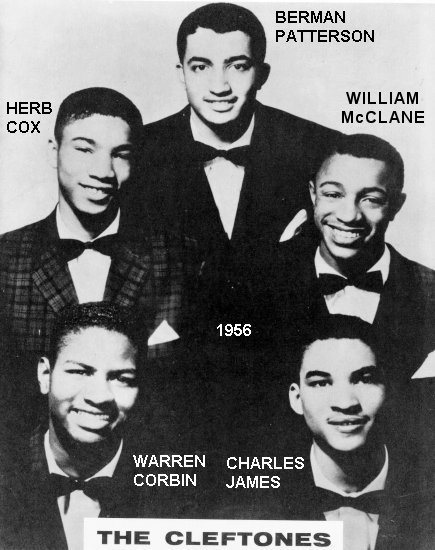

Please, in trying to explain the roots of this dangerously flawed man, stop referring to him as being from an “outer borough.” Also, please, stop the automatic segue into Archie Bunker and the grand old TV show, “All In The Family,” as if everybody in the borough of Queens sat around on a front step in a sleeveless undershirt and reminisced about the good old days of Herbert Hoover (or George Wallace, or Jefferson Davis, or Adolf Hitler.) As it happens, I grew up half a mile from the Trumps, although blessedly unaware of them for a long time. Friends of mine knew Fred Trump, his older brother, at PS 131, and said he was a lovely guy, but with learning disabilities. I met him a few times in the late ‘70s, and totally agree. That neighborhood is not exactly Bunkeresque. It is Jamaica Estates, an enclave of large homes, many of them on glacial hills just north of Hillside Avenue. When I was a kid, my parents would pack all five kids in the family sedan and drive around Jamaica Estates looking at the lavish Christmas decorations. My parents were Newspaper Guild activists, real lefties from the ‘30s. After the War, they helped form a discussion group, expressly 50 per cent black, 50 per cent white – idealistic bootstrappers from Queens, who talked about books and politics and life, sometimes in our living room. My parents loved Eleanor and Franklin, and praised Paul Robeson and Marian Anderson and Jackie Robinson. In later years, my parents voted at the same polling station as that lovely couple that had moved into Holliswood, Mario and Matilda Cuomo. Not exactly Archie Bunker country. I just looked it up: In milestone elections, Queens voted decisively for John F. Kennedy in 1960, Hubert Humphrey in 1968, Jimmy Carter in 1980, Bill Clinton in 1992, Al Gore in 2000, Barack Obama in 2008 – and Hillary Clinton in 2016. That’s right. The people who, theoretically knew their home boy best voted for Clinton, 75.4% to 21.8%. Queens has been consistent politically, even with all the changes. In the early 50’s, Jewish families were moving out from Brooklyn and the Bronx -- my new friends, settling into Tudor homes, reminisced about stickball games and six-story apartments in their old neighborhoods. There were few, or no, traces of Muslim or African-American or Asian families, part of the picture today. It was an enclave, but the nasty middle Trump brother missed it -- sent to private school in Kew Gardens (until he was caught packing a knife, and was shipped to boarding school, where goodness knows what transpired.) Most kids in Jamaica Estates went to Jamaica High – for me, a one-mile walk, via Henley Road, near the future TrumpHaus. Jamaica High was a bastion of academics but a mixed bag for equality. My friend Al Gibson recalls having to badger the “counselor” so he could take academic classes. (PS: He has advanced college degrees and a good career.) The nasty Trump boy missed this part of growing up: side-by-side with blacks. I served detentions with a black guy (college-bound) after we both thought it was fun to pester a young sub teacher. I shoved back at a black guy who constantly backed into me at the “good” basket in gym class. I also tried to guard Teddy Jackson, with that great first step, later a star at Hofstra – and still my lunch pal. Our yearbook advisor, Irma Rhodes (who rescued me in English class), held soirées for her staff at her home a few blocks from TrumpHaus; afterward I took the Q-17 bus with a young African-American woman, an art editor on the yearbook. All of this was superficial, of course, but part of the de-mythicizing of race. But the most integrated part of Jamaica was the choir/chorus of Jean Gollobin (one of the great leaders I have ever encountered in any discipline) who always had mature helpers like Carole Gardner, also a class officer. Five guys (P.A.L. basketball players from the 103rd Precinct) formed that early doo-wop group, The Cleftones, and would harmonize out in the hall, as if singing under the proverbial streetlamp. One of my classmates, Letty Cottin Pogrebin, has been a major force in the feminist movement; another, Sid Davidoff, has been a stalwart of Democratic politics; a third, Herb London, has been a conservative candidate. We all gained from the crowded halls and classrooms of a thriving public school. (The city gave up on Jamaica High a few years ago. Some of us keep thinking it will come back.) Life in the Jamaica area was and remains complex. The middle son of a builder was soon conniving with his father to exclude minorities from their buildings. He’d be doing it today, if he could get away with it. But please don’t tag all of us from Jamaica with the Bunker label. My daughter Laura Vecsey is a New Yorker. She loves upstate and she loved Seattle. But she’s a New Yorker.

Her only criticism of Seattle was that nobody talked. Non-verbal. An entire city. Maybe it was the rain. Or the e-culture. Or being the end of the line, south of Canada, east of the Pacific. We loved Seattle, too. If she had stayed, my wife and I might have moved there. But, geez, we are New Yorkers. She’s back on Long Island, horrifyingly aware that our “sleepy little fishing town” suburb is full of desperadoes who propel their fancy cars down the middle of narrow streets to express their rage at not being rich, or richer. Laura’s a writer (also a poet). She’s been driving her daughter to summer school in a town near us, where she recently discovered a really good little Afghan restaurant. Today she decided to do some reading in one of the many magnificent libraries in Nassau County. This is her stream-of-consciousness about the library: * * * by Laura Vecsey Working at the public library in Hicksville today. Walked into the building with a familiar sense of gratitude: We pay taxes and pass special levies to pay for these places to continue to exist. Sitting here for only a few minutes, in the air conditioning, with WiFi and outlet, amidst some book stacks and DVD collections, all I can hear are librarians talking at full volume; many unemployed 60-year-olds trying to master web applications on the free PCs offered. Lady next to me at the laptop desk drumming her long finger nails as she putzes around on her Kindle Fire. I don't see anyone reading a book. FYI. I'm going to go read one. (Now the librarians talking about how one of their colleagues orders too much food at lunch. ("You should just go with the soup.") THERE WILL BE NO WORK FOR ME TODAY! Also, this short stint in the library has already confirmed that New Yorkers, especially Long Islanders, really do talk ....a lot. I could have been in the Magnolia branch of the Seattle Public Library for 4 years before I heard this much talking. Make that 10, I mean. No one talks in Seattle. You have to use sign language in the libraries there or risk expulsion -- from the state. The conversation at the librarian station is now shifted from lunch and soup to ... acupunture. The lady with the Kindle Fire just said to me: "Why don't people whisper? I whisper when I'm here and all they do is talk loud over me!" I was not actually complaining as much as ....very aware that this IS a community space, not a study hall. And it is amazing the service residents are given. Questions answered. Resources for jobs, notaries, computer help ... it is indispensable stuff! It is also a fascinating place to observe what the heck people are up to and, frankly, how inept so many people are. I am not judging, per se. I am just ... amazed at how many things you assume people know … they don't. Hmmmm. Let me draw a parallel to the victory of a certain fraud elected to White House by these fellow Americans. ELITIST speaks! The Hicksville High School Tech Squad is giving a seminar on computer programming. I am not joking: About 28 of the 30 kids in there are ... of Indian or Pakistani descent. Which is why Hicksville is pretty cool these days. * * * (The bustle in our libraries includes English as second language, storytime for children, current events discussions, as well as computer training. I can order up books from the entire county system; a book on my desk is from East Meadow, one of the best-stocked in our county. And if there is a buzz, a hum, the services offered in our county more than make up for the my-half-out-of-the-middle SUVs and wagons blasting around our town. The suburbs pulse with life from recently-arrived cultures, people on the old main streets. We often drive half an hour to the thriving House of Dosas in Hicksville. Laura, who knew the best pho joints on Aurora in Seattle, has found Thai and Colombian and Afghan places in sleepy old Nassau County. She insists her family is moving upstate one of these years. What – and miss the Aush-E-Boreeda at the Afghan place?) Here is yet another poll I don’t want to hear. According to the highly-respected Quinnipiac Poll, residents of New York City prefer the Mets to the Yankees by 45-43 percent.

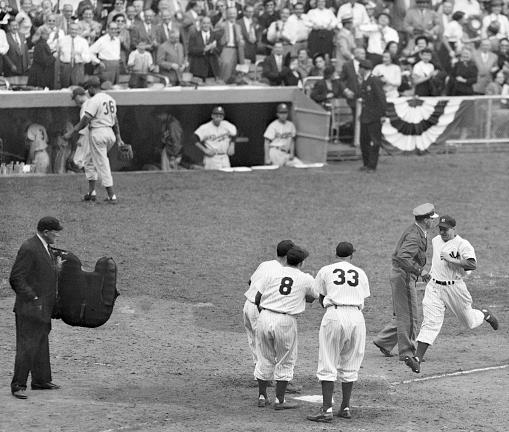

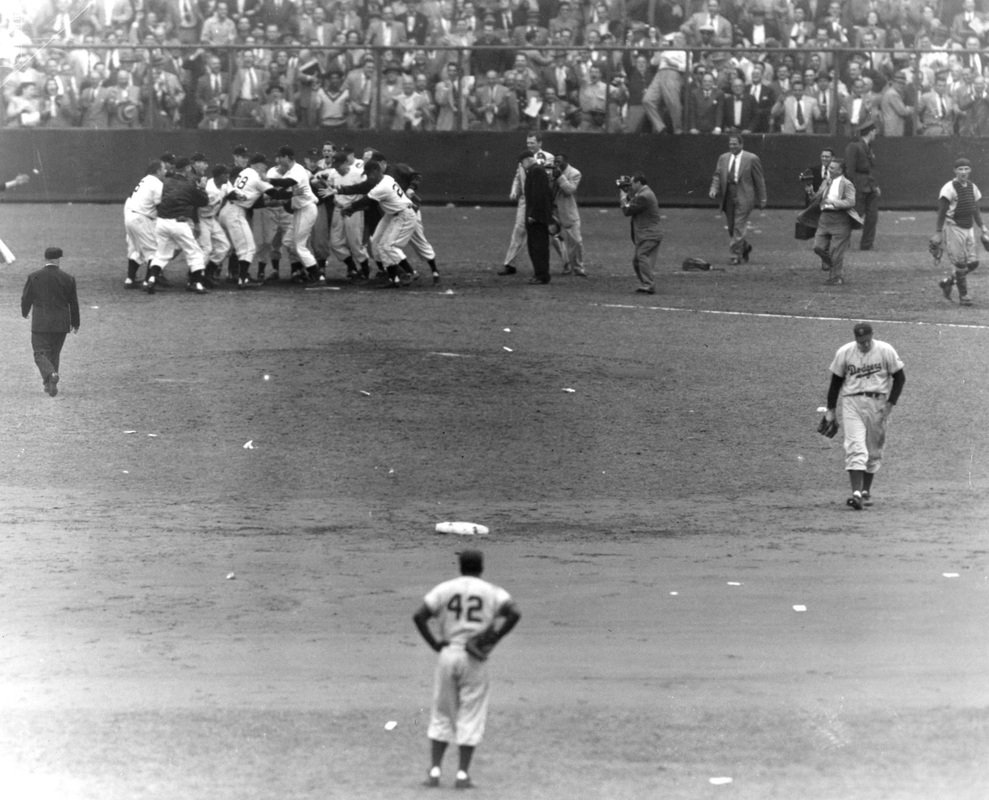

I’m a Met fan, totally out of the closet since retirement as a thoroughly impartial, you-never-could-tell sports columnist. I come by my National League/Long Island bias honestly as a boyhood Brooklyn Dodger fan who suffered terribly at the hands of the Yankees (to say nothing of, periodically, the New York Giants.) Quinnipiac is undoubtedly more correct when it says residents of New York State favor the Yankees by 48-34 percent. Those are the kind of odds I would have expected, what with all those World Series plus icons from Ruth and Gehrig to Jeter and Rivera. I have come to assume a lot of perfectly nice people have been swayed by the echoes in the “Big Ball Park in the Bronx” (Red Barber’s alliteration, not Mel Allen’s) and all those championships. Mets fans see their team as an occasional delightful surprise -- that World Series every decade or so, plus gallant efforts foiled by the 1987 Pendleton home run and the 1988 Scioscia home run and the 2006 Molina home run and the 2016 Inciarte catch – plus, the 2000 World Series when rich Yankee fans bought up huge swaths of Shea Stadium tickets. The gloomy words of George Orwell, personified. Now some New Yorkers may be swayed by all those fine young arms and the power of Céspedes and the dash of the prodigal son Reyes and the professionalism of Cabrera. Mets fans have expectations? Dangerous. I still want the Mets to be a minority taste which makes the Swoboda catch and the Mookie grounder all the more special. Then there is this: I don’t want my life guided by polls. Not anymore. Last autumn I was reassured by within-the-margin-of-error polls: the rational would squeak past the raging id. No more polls. * * * Play ball. Which the Yankees did, indoors, at Tampa Bay, on Sunday. By the second inning, I was immediately delighted with the fine details of baseball: -- Rays' LF Mallex Smith took a circular route but caught a fly in foul territory. -- Then, Smith (new to that team) took a piece of paper out of his pocket to scan the defensive scouting on the Yankees. Don't know that I've ever seen that. -- Between innings, the immortal voice of Bob Sheppard urged us -- stylishly, of course -- to follow the Yankees on the YES network. Nice touch. -- As starter Masahiro Tanaka faltered, he was watched intensely by three people in the Yankee dugout -- manager Joe Girardi, pitching coach Larry Rothschild and trainer Steve Donohue. Their faces told me: the real season has begun. Before I tell my Jimmy Breslin-Casey Stengel story, let's talk about bad timing for obituaries. (For example: Aldous Huxley and C.S. Lewis both died on Nov. 22, 1963.) Likewise, it is not a good career move to compete with Jimmy Breslin, “the outer-borough boulevardier of bilious persuasion,” as Dan Barry calls him. Chuck Berry died the same weekend as Breslin; the Times rolled out the big guns for his strut and the clanging of his guitar, outside the schoolhouse, urging boys and girls to come out and play. John Herbers was also honored with a Times obituary on Monday. He was 93, one of the great reporters of the civil-rights era, a gentleman all the way who politely treated me like an equal when I joined the national reporting staff. He had been in bad places – Emmett Till’s murder – and never lost the unassuming air of a small-town southerner. Bob McFadden and the Times did right by John Herbers: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/18/business/media/john-herbers-dead-times-correspondent.html Okay. Here’s my story about Jimmy Breslin, my fellow Queens boy. Elderly editors still marvel at his imagination in the wonderful interviews he turned in for $10 fees on long-forgotten sports magazines. In 1962 the New York newspapers acknowledged the Mets' raffish ineptitude early on. By late July Sports Illustrated dispatched Jimmy for his take on the worst team in the history of baseball. Breslin arrived in St. Louis the weekend of Casey Stengel’s 72nd birthday, and watched them bumble away games. One evening the club held a party for Casey in the rooftop room of the Chase-Park Plaza. Casey greeted the headwaiter, who had once tossed batting practice for visiting teams in the old Sportsmans Park. Casey imitated his motion, remembered his nickname. I was fascinated by Casey and never left his side all evening. Breslin was also there, observing. If anybody was taking notes, I do not remember. A year later, a Breslin book came out, entitled "Can't Anybody Here Play This Game?" a plea ostensibly uttered by Casey during his long monologue that evening in St. Louis. Not long afterward, Breslin called me for a phone number or something and at the end I said, "Jimmy, just curious, I was at that party for Casey, never left his side, and I don't remember him ever saying, 'Can't anybody here play this game?'" Long pause. "What are you, the F.B.I?" Breslin asked, his Queens accent turning “the” into “duh.” Years later, Breslin conceded he just might have exercised some creative license. Casey never complained about being misquoted. He would have said it if he had thought of it. That was the thing about Jimmy Breslin. He got the inner truths. He had an insight into people’s hearts, almost like a mystic or a psychic. Given his imperfections and his imaginations, he was a universal voice. He was also a very local voice. As the world becomes homogenized, we lose the local voices, the salt and the spices that make life exciting. (Fortunately for readers everywhere, Corey Kilgannon is covering Queens for the Times.) Chuck Berry caught the feel of Route 66 (“Well it winds from Chicago to L.A./More than 2000 miles all the way/Get your kicks on Route 66.” Makes you want to rev up the engine. John Herbers reported from the Deep South, which he loved and sometimes lamented. Jimmy Breslin understood Queens…and the world. He has not been well for years. I would have loved to read him on the scam artist from our home borough. * * * MUST READ: Dan Barry's personal tribute to Breslin on the NYT site: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/20/insider/dan-barry-way-back-with-jimmy-breslin.html?smid=fb-share Our friend Ina sent this video from a live French broadcast. World was never the same.

Carries the noise very well Carries the noise very well A colleague has spent part of the past decade wishing the subway construction would be over. Enough with the drilling and the rumbling. A few days ago, they flicked the switch for the Second Avenue subway. Her euphoria ended abruptly. “An all-night test has those of us facing Second Ave. most upset,” she reports. “The long escalators hum and the motion causes a vibration, which is felt even in my apt. (on an upper floor.) Worst of all we hear the trains rumbling past every six minutes.” Guess those artistic entrances allow the sound to escape. (As Casey Stengel said about artificial turf in the new St. Louis partk, 1966: "It sure holds the heat well.") “The stations look beautiful but we are quite sure the engineers on this project had never worked on a subway,” my colleague adds. “They should have studied the system in Paris. It is QUIET.” C’est vrai. The tires in the Paris Métro are made of rubber. So are the tires in Montréal. All right, so Second Ave. is not Paris or Montréal. We already knew that. But the planners don’t even know north from south. The sign for one exit: "The exit is at the NE corner,” my colleague said. “I told the mucky-mucks at the preview. They stared at me blankly.” There is a moral to the story as we try to escape 2016: New Yorkers used to snicker at the lumbering scam artist with the orange hair in our town. The vast majority of street-smart New Yorkers wished the guy would get a hobby and go practice it elsewhere. Ha!!! Meantime, Happy New Year. * * * But first, a little ditty from 1969: I look and listen for this man whenever I change subway lines at Roosevelt Ave. in Queens. I often find him midway on the Manhattan-bound platform, facing the E and F trains. In quiet moments I hear the melancholy strains of the erhu, a two-stringed Chinese violin. The chords convey the vastness of China, the long history, the pain, the hope. His own story, I do not know. He keeps his head down, plays to the beat from a mobile speaker. He puts a modest cardboard box between his sneakers. I stand up close. His China is not the neon-and-skyscraper China I encountered at the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, after they bulldozed most of the hutongs, the old neighborhoods. I take a few photos on my iPhone. He does not seem to notice. I drop $5 in the box and say “Xie Xie” -- thanks, in Mandarin. He says, “Thank you.” Then my train arrives. In the end, the Mets’ final game had nothing to do with ancient failures and curses on the Brooklyn Dodgers and early Mets. The Mets lost to a great pitcher, a great October pitcher.

I saw Madison Bumgarner’s expressionless face as he trudged out to the mound nine times. I was visiting my friends Gary and Nancy, and I explained to them that he was a mountain man from western North Carolina, neither north nor south but Appalachian. He had a job to do, and he had the tools to do it. Later, when the job was done, he submitted to an interview, and I could hear the mountain accent; he comes from a hamlet full of Bumgarners, for generations. One tough, self-reliant dude, with great arm, great purpose. My friend Big Al from Queens, who used to pitch off the scruffy mound in Alley Pond Park, wrote me this morning that as a former hurler he marveled that Syndergaard could bust in 98- mph fastballs, with admirable location, but that Bumgarner’s 92-mph pitchers went even more precisely to the right place, where Céspedes and others could not harm him. Big Al thinks Bumgarner could have gone 11 or 12. I’m just sorry it was Familia at the end. He’s such a nice guy, gave us such a good season. Then there is Granderson’s catch. He is already the favorite Met to so many people. (I know a few women who refer to him as “my boyfriend” when he smiles and hits home runs.) On Wednesday night he ran straight to the center-field fence knowing he could make contact, and he held the ball for the third out. My son David wants to know how Granderson’s catch compares with Endy Chavez in 2006 and Tommie Agee and Rocky Swoboda in 1969, and I say quite equally. Big Al had to bring up – he always does this – Mantle’s catch off Hodges to preserve Don Larsen’s perfect game in 1956, and I retort with names like Gionfriddo from 1947 and Amoros from 1955. But that’s old stuff. Right now it is 2016 and Bumgarner evokes names like Ford and Gibson and Koufax. For me, la guerre est finie. I got no dog in this fight from here on in. I’ve seen all the baseball I want for this lovely surprising gritty season of the Mets. I’m checking up on the Premiership and Serie A, and books, and classical music. Big Al suggests Chopin and Schubert. I’m thinking Dvorak and Bartok. As we said in Brooklyn, wait til next year. (Your comments on the game and 2016 are welcome; my earlier premonitions of gloom and doom are below.) Brian Savin asks if I have any thoughts about the Mets in the wild-card game Wednesday. Oh, yes, doctor, I have thoughts. I also have fear and trembling on this 65th anniversary of something terrible. It happens every October, when I feel that something terrible is going to happen in a ball park near me. I mean, it’s only baseball terrible. Henrich terrible. Thomson terrible. Sojo terrible. Molina terrible. This has nothing to do with Syndergaard vs. Bumgarner, Mets vs. SF Giants. They are on their own and will perform what they perform. I am talking about the miasma of gloom that hangs over an old, I mean old, Brooklyn Dodger fan at this time of year. Let’s start with Oct. 5, 1949, first game of the World Series (still played in sunlight, before the current long march toward freaking November.) I race home from school, turn on the radio, just in time for the bottom of the ninth, and Tommy Henrich blasts a homer off Don Newcombe, first and only run of the day. Traumatic? And not just me. Let us fast forward half a century or so. My good friend and Newsday colleague Steve Jacobson is typing in the press room of Yankee Stadium on old-timers day. He sees Tommy Henrich, still spry, heading toward the men’s room. Steve accuses Henrich of ruining his childhood with that home run. From that point on, Steve laments, he could no longer study, and therefore had to drift into the sordid life of sports columnist. “Tough shit,” Henrich says genially. “What were you going to be, a doctor?” (Perfect Noo Yawk inflections and gestures.) And like a man taking a trot around the bases, Henrich continues to the men’s room. Next stop: Oct. 3, 1951. I am in shop class in junior high. The teacher lets us put on the radio. My Dodgers have a lead on the annoying New York Giants in the third game of a playoff for the pennant. A classmate, a Yankee fan, says, “I can’t imagine how you will come to school tomorrow if the Dodgers lose.” I take the subway home. Bobby Thomson hits a home run. Perhaps you have heard of it. I go to school the next day. Giants fans and Yankee fans jeer at me. The only good that comes of it is Don DeLillo’s great “Pafko at the Wall” segment of the otherwise murky (to me) novel, “Underworld.” Later, the New York Mets will be formed, and the collective angst of the Dodgers and Giants will be infused into the Mets’ DNA. The Mets will know glory in October, but also despair, as in 2000 when Yankee fans outnumber Mets fans for World Series games in Shea Stadium and Luis Sojo dribbles a crushing hit up the middle, and in 2006 when Yadier Molina hits a two-run homer as the Cardinals beat the Mets for the pennant. Now my friend asks if I have any thoughts about the Mets’ game on Wednesday. This has been one of the most enjoyable baseball seasons I have ever had, with the Mets playing beyond all hopes and expectations in the final six weeks or so. I will always glory in Granderson and TJ Rivera, Cabrera and Familia, and the prodigal son Reyes. But I am writing this on the 65th anniversary of Bobby Thomson. The game will be played on the 67th anniversary of Tommy Henrich. I have thoughts.  Once House of Horrors, Now Practice Court for John Isner; Next Year, Gone. Once House of Horrors, Now Practice Court for John Isner; Next Year, Gone. Strictly by coincidence, the Times has a feature on the Op-Ed Page Saturday about the vanishing storefronts of New York, victims of rising rents. I was already planning my ode to the vanishing landmark of Queens, the house of upsets, the cramped, smoky pit known as the Grandstand. Once upon a time it was the second court at the United States Open, an afterthought grafted onto the main arena, Louis Armstrong Stadium, itself a tennis improv. But now in the name of modernity, the Grandstand has been phased out. It is serving as Practice Court 6 for this year’s Open but then will be bulldozed, gone, like ancient temples destroyed by vandals. The Open is one of the two best sporting events in my home-town, along with the one-day phenomenon of the Marathon in the fall. I can look past the money and the privilege and see the Open, with its roots at the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills, as still very much a Queens event, right off the No. 7 elevated train. This year the Open has a new retractable roof over Ashe Stadium to keep the show moving when the monsoon hits. The Armstrong will be replaced by a new second stadium. The Open also has a new generic bowl, called the Grandstand with 8,200 seats. I am sure it has more amenities than the old Grandstand but it does not exactly have the feel of an Elizabethan bear-baiting den. For many years, the players had to inhale the meaty fumes from a restaurant suspended above the west stands. Something was always out to get the favorite at the Grandstand: In 1985, Kevin Curren, the fifth-seeded player from South Africa, was bumped off in the first round by upcoming young Guy Forget of France. Curren promptly emitted a Hope Solo solo, blaming the site for his troubles. “I hate the city, the environment and Flushing Meadow,” Curren said. “There is noise, the people in the grandstand are never seated and it takes an hour and a half in traffic to get here. It’s sickening that with all the money they get from TV, the USTA doesn’t build a better facility. The USTA should be shot. And they should drop an A-bomb on the place.” Curren was not the only player to get bushwhacked in the Grandstand. On Friday I ran into a former player who had benefited from the blood lust of the fans. In 1981, Andrea Leand, all of 17, met second-seeded Andrea Jaeger in the second round – in the Grandstand. “Andrea was up a set and 5-2,” Leand recalled. “I could hear a broadcaster saying, ‘That’s it, she’s done.’” Then again, you could hear everything in the Grandstand. “I heard a man asking his son, ‘Do you want a hot dog?’” The mob began howling for a new victim to be sacrificed to the Grandstand deities. “The sound went right through you,” Leand recalled with a beatific smile. She beat Jaeger, 1-6, 7-5, 6-3. It could happen to anybody, and often did. The litany of Grandstand upsets is long – best left to an expert like Randy Walker, who last year wrote a farewell to the Grandstand, well worth reading: The great thing about the ramshackle center of the 80’s was that reporters could watch Grandstand matches from the back of the press box in the main stadium. One match turned into a heavyweight fight -- Roscoe Tanner, one of the hardest hitters on the tour, and Chip Hooper, a big fellow, trying to drill each other, up close and apparently quite personal. This being the yappy borough of Queens -- Trump! McEnroe! Archie Bunker! -- the fans egged them on. Competition was also nasty in the lines as fans tried to get into a match that had suddenly turned epic. I visited the old den the other day – a few fans watching John Isner and a hitting partner whacking the ball around, but no yelps from fans seeking a new victim. The Grandstand could have served forever as an anarchic, irregular heirloom – a tribute to history. But Open executives can still revive the gritty aura of the old place: pipe fumes from the grille directly onto the court. Kevin Curren would feel right at home. Ted Cruz, the lawyer who scorns election ambiguities and disclosure rules, also scorns “New York values.”

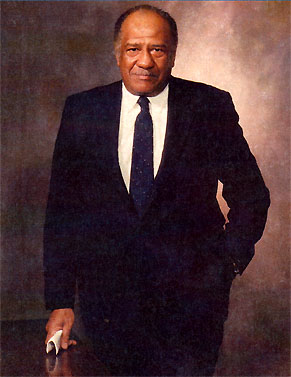

We know what Cruz is doing – going after the evangelical vote by raising that old specter, the urban type, with noses and accents and odd names and weird food tastes. You know. The city where America’s children go if they think they can make it there. Cruz was going after Donald Trump – and welcome to that – by making him typical of New York. But as somebody who grew up a crucial half mile from the Trumps, I have to admit, the Donald, in his own vulgar way, represents a sub-group, his home borough of Queens. Simon & Garfunkel. 50 Cent. My Jamaica High chorus members, The Cleftones, who played PAL basketball for the 103rd Precinct. Bernadette Peters. And I remember my friend’s older sister, when I was 10 or so, raving about “that Tony Benedetto from Astoria”. The man is still singing, but now to Lady Gaga. Many of us from Queens form a yappy lot. Is it the vital separation from “The City” – Manhattan? Looie Carnesecca, for many years from Jamaica Estates, says New York pizza is the best because of the water. Is it the brackish water of Flushing Bay and Jamaica Bay and Newtown Creek that makes Queens people tend to mouth off? Or is it the relative space and light that grows characters? John McEnroe. Jimmy Breslin. Howard Stern. Fran Drescher. Christopher Walken. Trump is a mouthy rich boy, but Cruz prodded him into the first dignified moment of his campaign, maybe of his life. Trump stuck up for us, the people with the New York values. Athletes? The common ingredient of Queens jocks is the need to handle the ball. Point guards. Control freaks. Bob Cousy-Dick McGuire-Kenny Anderson-Kenny Smith- Mark Jackson-Nancy Lieberman, who took the A train from Far Rockaway to Harlem to get a game. Peter Vecsey, who played for Molloy and writes about hoopsters. And from Jamaica High and St. John’s, Alan Seiden, known in the P.S. 26 schoolyard as “And One,” because he called a foul every time he took a shot. Bob Beamon, from Jamaica High, was a dunker, not a passer. He could leap. Leaped to a world long jump record in Mexico in 1968. The thing about Queens is that the subway and elevated lines all head west, toward The City. I remember slouching in class at JHS 157 in Rego Park, watching the No. 7 El rumble toward The City. Trump lived a few blocks from the last stop on the F Line but I wouldn’t bet he ever took the train. Probably got chauffeured to his prep schools. With all this glorious diversity around him, somewhere along the line Trump developed outsize prejudices. This tells me he never spent much time with Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard. He would have a different facial look if he had. Queens College graduates: Jerry Seinfeld. Ray Romano. Howie Rose, Mets voice. Cruz is playing to the base, the red-hots who cheered him in South Carolina and might caucus for him in Iowa on Feb. 1. His code words of “New York values” are an insult to the Chinese in Flushing and the Koreans along Northern Blvd. and the Latinos around 82nd St. and the South Asians around 74th St. -- and my friend Alton Gibson from South Jamaica who disregarded his guidance counselor’s advice to take vocational classes, and got himself advanced degrees and a good career. Those New York values. Mario Cuomo from South Jamaica who married the beautiful Matilda Raffa and led a life of good works and talented children. In Queens, we talk and write and sing and dream. Letty Cottin Pogrebin. Stephen Jay Gould. Stephen Dunn, zone-busting guard and Pulitzer Prize winning poet. Francis Ford Coppola. Sam Toperoff. Lucy Liu. Russell Simmons. Idina Menzel. Michael Landon. Cyndi Lauper. Joe Austin, Mario Cuomo’s coach for life. The bright young woman from the English class in Jamaica High a decade ago, now a college graduate doing advance work for Bernie Sanders in New Hampshire. The bright young woman from two decades ago, now getting her teaching certificate in the grand building on the hill. Those voices Those accents. The great spices emanating from open doors and adjacent apartments in Astoria and Bayside and Hollis and Ozone Park. The dreams. The drives. The New York values. I associate Roger Cohen with his skateboarding on a small ottoman, at risk of a broken neck, to celebrate a Chelsea goal on the tube.

I associate Tracy Kidder with his long legs racing around the bases on a softball party, decades ago. Yes, serious writers, have their sports side. I just caught up with books by both of them, touching the deepest issues in the world – genocide, inequity, identity. Cohen’s book is “The Girl from Human Street: Ghosts of Memory in a Jewish Family,” published this year by Alfred A, Knopf. It is partially about the imbalance in many members of his family, which has made the trek from Lithuania to South Africa and onward. His mother became troubled shortly after emigrating from South Africa to England early in her marriage and never recovered. The book also delves into what it means to be Jewish in a dangerous world, with some of his family escaping ahead of the murders in Europe, making a success in South Africa, but never feeling quite accepted in England – hearing the discreet lowering of voices and being described as “Jew” rather than “Jewish.” Later Cohen re-settled, for reasons he came to understand. “One day, banking over New York City on the approach to LaGuardia, watching the serried towers of midtown, a single word welled up from deep inside me: home.” Cohen writes of the city of “incomers.” He has become one of journalism’s most staunch defenders of the marginal. Tracy Kidder has also been exploring corners of the world, ranging from the emerging computer society to poverty in Haiti, often seeking people who take chances, who make a difference. His idealism is on display in his 2009 book for Random House, “Strength in What Remains: A Journey of Remembrance and Forgiveness.” Kidder traces the wandering of a people, and an individual, Deogratias Niyizonkiza, a member of the Tutsi tribe in Burundi. Barely escaping a bloodbath while in medical school, Deo survives in Africa the same way some of Cohen’s family survived in Europe – through the grace and courage of others. In Kidder’s book, the man called Deo lands in New York, is helped by a baggage handler named Muhammad, a former nun, and an intellectual couple from Greenwich Village – the parallel layers of strength that work so often in this city. Kidder recreates Deo’s survival in Burundi, and moves toward the present, with Deo, now a poised 40-something New Yorker, running a medical facility back home in Burundi, where the prevailing custom is to not remember terrible things that have happened. My conclusion is that there is no such thing as light summer reading. These books by Cohen and Kidder would make me think and care in any season.  Lauren Bacall loved this box. She told Cornell's biographer, "I wish I had it." Lauren Bacall loved this box. She told Cornell's biographer, "I wish I had it." Joseph Cornell was already well known for his collages in small boxes during the mid-50’s when I was in high school. Our busy road (188th St.) dead-ends into Utopia Parkway just south of Cornell’s home, maybe three miles from my childhood home, but I don’t remember my cultured friends and teachers ever mentioning him. The Jamaica High School paper interviewed famous New York people and probably could have gained an interview with this introverted soul but, like me, the editors had not discovered him. I am thinking about Cornell because my daughter Laura just took his biography – “Utopia Parkway: The Life and Work of Joseph Cornell,” by Deborah Solomon -- out of the library. It’s been around since 1997 yet it took me this long to read about this artist who lived with his widowed mother and his younger brother who was limited by cerebral palsy. Cornell is stereotyped as the hermit who stayed home on Utopia Parkway, caring for his mother and brother, and when the world quieted down at night he would snip others’ work and blend them with memorabilia of France, or incongruous mundane objects to create new form. I once met Louise Nevelson at a party. She made us roar by describing how she bellied into a dumpster to retrieve some artifact she could use in her sculpture. Cornell was no less driven. Somehow, he managed to work at menial jobs in the city, to support his family, while haunting the art galleries and bookstores at lunch hour and then take the train back to Flushing. People called him a a recluse but really he was a Zelig of an Outer Borough who knew Dali and Duchamp and de Kooning. Tony Curtis came to his house in a limo! Cornell sought out ballerinas and actresses, shopgirls and students. Audrey Hepburn sent back one of his boxes. Susan Sontag enjoyed his company. His work celebrates sensuality, small hotels in Paris, birds, mystery, beautiful women. He died in 1972 at the age of 69. The author informs us that his short, intense crushes were "platonic." I liked Cornell even better when I read that he loved the haunting music of Erik Satie, who lived in a squalid little flat in the outback of Paris. Cornell's boxes and Satie's compositions are a perfect fit. I have loved Cornell's work since my wife, an artist, introduced me to museums and galleries. Maybe I am particularly affected because I grew up in Queens, in a narrow house much like Cornell's. Next door, a few feet away, two brothers, waiters named Rocco and Luigi, practiced the scales and the arias on summer afternoons with the windows open, before going to work. In Queens, we knew that “it” was just a subway ride away. And all that time, maybe three miles up the road, Joseph Cornell was caring for his family and making his boxes. There is not a single statue of a real woman in Central Park. Good grief.

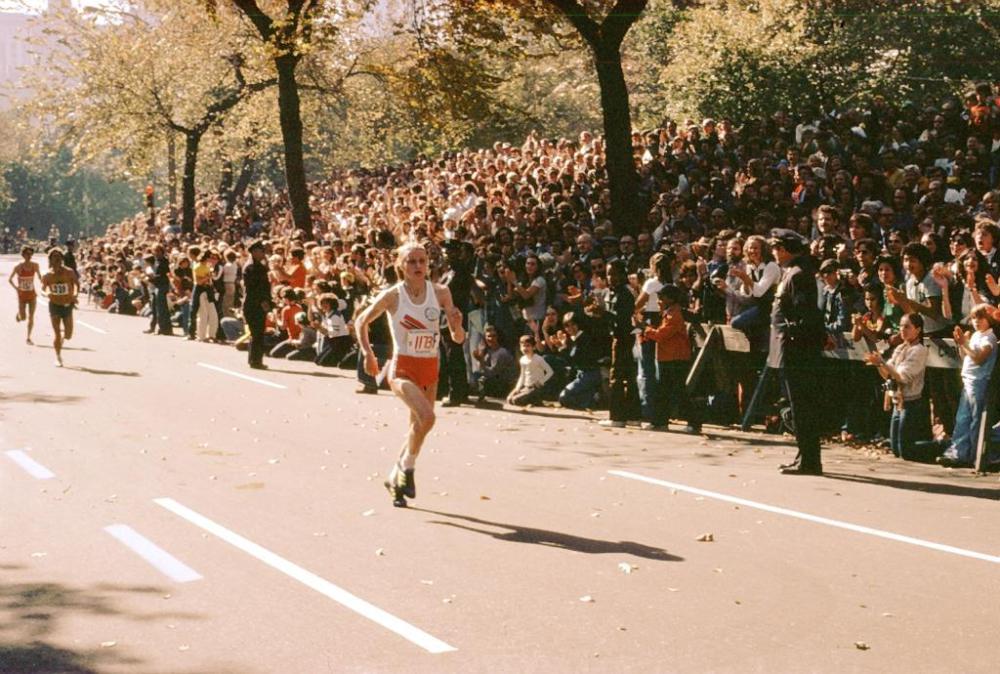

I did not know that until Thursday when Jami Floyd did a segment on WNYC-FM about this ludicrous injustice. Juliet of Verona. Mother Goose. Forty-four statues of men, but none of women who actually walked this earth. . My first response was, of course, Grete Waitz. She flitted through the streets of New York like a super-powered sprite from Norway, nine times ending up in Central Park as the winner of the New York Marathon. And still no statue? One could argue that her athletic achievement was the greatest by a female athlete within the borders of the big city. She owned the town, nine Sundays in November. She set an example of talent, grace and will, and New Yorkers claim her, despite the statue of her in Oslo. Waitz passed way too young in 2011, at the age of 57. She remains the embodiment of the sport. Men and women think about her when they put one foot after another. I know there is a statue of Fred Lebow, the big macher who built the New York Marathon, on the east side of Central Park. I jogged a few miles alongside them, through Brooklyn, in 1992, the day Waitz escorted Lebow, who was dying of brain cancer, on his last run around the city. But this is no time for Tracy-and-Hepburn sentiment. Waitz deserves her own statue, right near the finish line on the west side of the park. Obviously, there are hundreds of deserving women to right this wrong. My mom is out there, telling me, “Eleanor Roosevelt! Dorothy Day! Marian Anderson!" People were calling WNYC, nominating Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Marie Curie, Jackie Kennedy, dozens of worthy people. Nobody ever ruled Central Park the way Grete Waitz did. In a New York minute, get her a statue. Bob Goldsholl once saw two teammates squabbling over a uniform -- with No. 9 on the back.

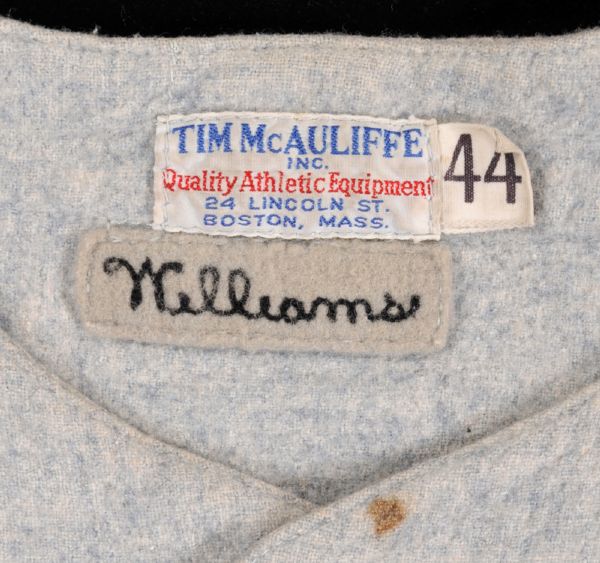

This memory came flooding back as New York University begins its first baseball season since 1974. Goldsholl, a retired New York sports broadcaster, pitched NYU into the College World Series in 1956, wearing a hand-me-down uniform from a certain team in Boston. The venerable NYU coach, Bill McCarthy, had friends with the Red Sox, ranging from a scout to the owner, Tom Yawkey. Every year, the Red Sox shipped used uniforms to NYU, which led a couple of top dogs to bicker over Ted Williams’ elongated uniform. (The team name was altered on the front.) Those were great days for baseball in New York – three teams in the major leagues and seven local rivals in the Metropolitan Conference – City College, Wagner, Brooklyn, St. John’s, Hofstra, Manhattan and NYU. Personal note: As the student publicist for Hofstra, I sat on the bench, kept score and heckled the other team. The St. John’s players used to shout, “Shut up, Pencil.” Three players I saw made the majors – Chuck Schilling of Manhat-tan, Ted Schreiber of St. John’s and Brant Alyea of Hofstra. From the home-and-home series, you got to know the players in the Met Conference. City College had a squat little center fielder named Tim Sullivan who bravely wore No. 7 in a city with another outfielder bearing that number, and a junk-balling lefty named Lubomir Mlynar. (My Hofstra guys made fun of his nose and his name and his stuff – but they could hardly hit him.) City College had an all-star third baseman, Weiss, who had missed a scholarship to NYU because of a bureaucratic slipup. He savored playing his good friend, Jerome Umano, the shortstop, whose NYU uniform had Johnny Pesky’s name sewed inside. (Weiss would play well into his 70’s in adult hardball leagues, and is currently featured in a book about New York and baseball, Penance and Pinstripes: The Life Story of Ex-Yankee John Malangone, by Michael Harrison.) NYU had a great history, sending Ralph Branca to the majors plus Eddie Yost, Sam Mele and my good friend, a two-sport star, Al Campanis, who had a war-time cameo with the Dodgers. They played on the uptown campus, right next to the Hall of Fame. No New York team had ever reached the College World Series in Omaha until Goldsholl and Art Steeb pitched NYU there in 1956. “I was warming up in Omaha before our first game against Arizona,” Goldsholl said Thursday. “The public-address announcer introduced the squads -- NYU, with a record of 16-4-1 and the University of Arizona, with a record of 45-6.” Struck by the ludicrous disparity between northern baseball and southern baseball, Goldsholl said, “I just stopped throwing and started to laugh.” NYU lost to Arizona and Wyoming. Goldsholl played two years in the Giants’ system, and later became a familiar New York voice. NYU gave up baseball after 1974 and moved from Division I to Division III and consolidated (to say the least) its presence in Greenwich Village. The new players need not inspect their uniforms for any Red Sox names. Myrtle Avenue. Even before Saturday, the name made me hear the terrible sound of police knuckles against steel lockers in the back room of the station house, the curses and the cries and the helplessness.

That memory is from the dark days of January of 1973, when a police officer was killed on duty under bisecting elevated trains at the intersection of Myrtle and Broadway in the Bushwick neighborhood. Last Saturday it happened again, four blocks away at the corner of Tompkins and Myrtle, in adjacent Bedford-Stuyvesant. Two officers were assassinated as they sat in their car. It never ends. In 1973, Officer Stephen R. Gilroy was killed during a botched robbery at a sporting goods store, when four young men, caught up in an American Black Muslim rivalry, had tried to arm themselves. For two days, the Bushwick neighborhood was shut down, power to the El cut off. But no more shots were fired because one of the great cops of New York, Deputy Commissioner Benjamin Ward, used modern siege tactics to wait out the men inside. At 1 o’clock on a Sunday afternoon, promised they would not be gunned down, the men surrendered. As part of the huge Times contingent that weekend, I was posted at the station house when three of the men (one went to the hospital) were booked, as officers pounded their lockers in frustration. I also covered Stephen Gilroy’s funeral a few days later. To this day, I cannot hear bagpipes without thinking of the family coming out of the handsome old church in Brooklyn. This year Americans have learned about senseless deaths in Ferguson, Mo., and Staten Island. I’ve read the stories, seen the videos, heard the interviews, parsed the testimony, second-guessed the grand jury work. My conclusion is that the tactics that Benjamin Ward espoused – patience, logic, fairness, rules, and, yes, toughness – would have kept Michael Brown and Eric Garner very much alive. Benjamin Ward later became New York's first African-American police commissioner. I thought of him this summer when I visited the intersection of Myrtle and Broadway. Somebody is doing a reprise of the siege, and I was dredging up my memories, as one of the younger reporters on the scene that sad weekend. In late August young (white) people were clumping down the steep staircase from the El, lugging roller suitcases, moving into Bushwick, to rehabbed houses on side streets. I had lunch in a hipster place where they served crispy kale. The sporting goods store is now a peluqueria – a hair salon. All 12 chairs were busy on a summer Saturday morning. Life was going on. In the wake of Brown and Garner and other needless deaths, most protests have been peaceful, as if people had heard of Gandhi and King and John Lewis, but on the nearby Brooklyn Bridge somebody threw a garbage can at police and others jumped cops who were keeping the peace. All I know is, Violence begets violence. I was going to write something about world politics, or Derek Jeter, or Gail Collins’ column on climate, or why it is raining in New York, when the Jewish holy days are supposed to bring gorgeous fall weather, or my friend from junior high school who is becoming a rabbi.

Instead, I am sending a photo from our granddaughter Anjali, currently visiting family in the north woods. Shana Tova Guess I picked the wrong month to brag about not being a snowbird, to revel in staying home in New York, with the glory of the seasons, which would include winter. I was so proud of having all that culture and entertainment a few miles to the west. We have tickets to Symphony Space to see the film of the Bennett play from the National Theatre. It’s around 10 degrees outside. I don’t think we’re getting out of our driveway. # # # (My little riff on snowbirding the other day)

We read in the Times the other day that Florida is supplanting New York as the third most populous state. I can exclusively reveal here that I am not joining the exodus. We tried snowbirding in Florida 20 years ago, and it didn’t take. My wife made a splendid discovery of a low-slung condo in Boca Raton with a gorgeous view of the blue-green ocean, on the theory that it was halfway between the Yankee spring camp in Fort Lauderdale and the Mets’ camp in that wasteland of Port St. Lucie. I would get up in the morning, take a delightful jog and then have breakfast and read the paper and take a shower and notice it was 10 o’clock in the morning, and what the hell was I going to do with the rest of the day? I never did figure it out. Maybe we were too young. Fifty. We found concerts in Miami and an Indian restaurant in Coral Gables and strong coffee on Calle Ocho and a Thai restaurant in Boca. One night in a restaurant my son-in-law pointed out a well-known gangster, warily sitting with a view of the front door. I thought he was in hiding. Most people we met had a murky story – new name, new face, new fingerprints, new spouse. Everybody seemed to come from somewhere else. Many of the people in our complex were from Ohio, Michigan and Ontario. I found myself hanging out at the guardhouse with a Cuban guard from Miami and an Italian guard from Brooklyn. We told stories and laughed. Sal the handyman had coached Craig Biggio in Little League back on Long Island. We talked baseball. My wife and I kept the blinds open at night because of the direct view of the ocean. But I would be awakened by the reflection in the mirror of the blinking red lights of ambulances visiting the complex. Ask not for whom the light blinks. Commuting from work in New York, I began to have vivid dreams of slush and sleet and snow and fog and drizzle. The plane home would emerge from the clouds and screech to a landing at dank gelid LaGuardia and I would go, Yessssss! So we sold. I still love Florida to visit – the Vietnamese restaurant in Orlando, rice and beans in Ybor City, funky downtown St. Pete, looking for Casey Stengel. But I’m paying the horrendous taxes in New York. It’s home. Everybody needs to know where home is. I know Florida for its election scandal of 2000 and its unsavory Gov. Scott and the Trayvon Martin tragedy. But I’m not worried if Florida gains a seat in the House and New York loses one. I turn on the tube and I hear Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz, who sounds like all the girls in my junior high school in Rego Park, Queens -- and no wonder, she’s originally from Forest Hills -- and Rep. Alan Grayson, who reminds me of classmates at Jamaica High -- and no wonder, Grayson is from Bronx Science. Billy Donovan coaches at Florida. Donna Shalala runs the University of Miami. We are exporting clear-thinking strong personalities just to help our friends in Florida. Some of us are staying behind. The weather was gorgeous. Of course it was.

We were sitting up front in the Mykonos restaurant in Great Neck. The windows were out so patrons could enjoy the traditional glorious weather of the holy days. The Lubavitchers were walking to their Chabad, the men in suits, some of them tropical white, the women in dresses. This was a week ago, the second evening of Rosh Hashanah. A cluster of young people, boys and girls, stopped in front of our table. A young man, maybe 12 or 13, surveyed our table of four and asked the classic question, often posed by proselytizing men in the city: “You Jewish?” We glanced at Mike, our DH (Designated Hebrew, to use Ron Blomberg’s felicitous book title.) “Have you heard the shofar yet today?” the young man asked. (The shofar is the ram’s horn, blown all over the world at the Jewish new year.) Mike had been to temple in New York, but he was not about to spoil a good scene. No, we all said. The one adult in the group, I am assuming a rabbi, began to blow on the horn, for two or three minutes, his notes undoubtedly reaching the shopping mall across the street. Then he led Mike in a Rosh Hashanah prayer, as all four of us joined in. They wished us not only a good Rosh Hashanah but a sweet Rosh Hashanah. A good Rosh Hashanah could sound like a root canal, the rabbi said. But Rosh Hashanah should also be sweet. The young people smiled sweetly and we thanked them, and then they were gone. The manager brought our dinner, just perfect, like New York weather at the holy days. The link is Jamaica High School, built to last forever, high on a glacial hill.

The White family moved into the house in 1938. Jean White was our class president for 1956, a born leader. President for Life, we call her. Jean was captain of the cheerleaders when her boy friend Eddie Grenning played for Brooklyn Tech against Jamaica, in the PSAL semifinals in 1955. Then she led the cheers for Alan Seiden and Artie Benoit as Jamaica won the title. When Eddie passed, way too young, Jean sought out adventures, getting air-lifted onto a remote island in Alaska, where she spent a winter working as a community liaison. Now she lives on another island, called Manhattan. A few weeks ago, Jean White Grenning was in the old neighborhood and decided to take a look at her childhood home, which the Whites had sold to the Forrestals in 1977. Jackie Forrestal sent her daughter Kathy to Jamaica High, where she worked on the school paper, the Hilltopper, and loved her time there. On this spring day, Jackie and Kathy were both gardening in the front yard when Jean dropped by. So much history in that meeting. Jackie has become a leading activist, sticking up for the legacy of Jamaica High, as the city, in a fit of Pol Pot nihilism, has sought to destroy the landmark high schools. Jamaica High is being phased out, with the gorgeous indestructible building turned over to the new fad in education, boutique mini-schools. In its time, Jamaica nurtured Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, Democrat from Houston, Letty Cottin Pogrebin, Stephen Jay Gould, Bob Beamon, epic Olympic long-jumper, Paul Bowles, Sid Davidoff and Herb London. Four friends of mine, who lived a few blocks from each other, became doctors, some still working. The last legal hopes for Jamaica High are stalled somewhere in the court system; Jackie Forrestal goes to meetings, reminding people that her daughter Kathy had a great time in Jamaica not so long ago. Jackie has come to be the caretaker for bound issues of the Hilltopper, our school paper, and other treasures, just in case the school somehow emerges from this dark age. A few weeks ago, Jean White Grenning and her brother Stuart White took the subway to Parsons Blvd and walked up 164th St., visiting their old church, the First Methodist Church of Jamaica. “The minister graciously showed us around the church and explained that he would be leaving for another church in South Jamaica. In general, he said, church attendance is down all over.” They stopped in the old candy store, now a deli, and talked to new owner who has been there six years. Then they visited their old house, a few blocks from Jamaica High, and Jackie showed them around the house “which looks the same to us. We then walked to Union Turnpike stopped in another deli (now Korean) and peeked into the windows of Dante's which did not open until 4 o'clock.” (Back in the day, Dante’s was a mere pizzeria, where everybody went after the basketball games.) Jean and her brother walked up 168th St. to Jamaica High, where they chatted with a few boys in one science-oriented mini-school. “They were unsure if they liked the smaller school and thought maybe they would like a bigger school,” she said. The neighborhood has changed; there is a bustling mosque on 168th St. A few years ago, I had a great time visiting some classes at the old school; I felt Jamaica High was still producing strong people like the Whites and the Forrestals. Editing papers at Jamaica High and Dartmouth College, Larry Sills dreamed of working for The New York Times. Instead, he went into the family manufacturing business.

The next thing I heard, Sills was the focus of a terrific article in the Atlantic in January, about a company that still makes things right here in the United States. If you want to jump immediately to the article by Adam Davidson, I would encourage you to do so. http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2012/01/making-it-in-america/8844/ I was told about the article by the Hon. Walter Schwartz, my lawyer and friend -- otherwise known as Chief -- the editor of the Hilltopper in our senior year at Jamaica. Sills was the sports editor who gave up his column and assigned me to take over. I hope I remembered to thank both of them for giving me a start. Schwartz and I visited Standard Motor Products the other day. The Sills family used to own the six-story factory on Northern Blvd., but now leases the airy top floor. Sills told us how the recession has challenged his company, but he continues to produce things in Greenville, S.C. and elsewhere. He paused and pointed to the ceiling. “There’s a farm up there,” he said, telling us how the landlord arranged for the Brooklyn Grange to run a one-acre farm on the roof. Sills described how a crane lifted tons of dirt and a tractor onto what New Yorkers used to call Tar Beach. He winced as he recalled the concussion of the tractor spreading dirt a few inches above his curly head. We climbed a flight of stairs to the farm, where four or five nimble college-age people were doing what farmers do. There was also a photo shoot going on, with an actual model; we tried to stay out of her way. Sills pointed out the skyline of Manhattan, plus the tomato and pepper plants, and early shoots of sunflowers which, in a few weeks will reach our height. He pointed out several bee hives in one corner and laughed about how the bees took a ramble one day, blocking traffic on the busy street below. He showed us the chicken coop. Every Wednesday, he said, Brooklyn Grange holds a public market in the lobby, in front of the art display. We took a short drive to Zenon Taverna in nearby Astoria, for some excellent grilled fish, celebrating this ethnic borough. Sills and Schwartz and I discussed our college newspaper careers at Dartmouth, City College and Hofstra, respectively. As it turns out, Larry and I both chose industries currently being challenged in this new economy. He did not display any remorse about heeding the tug of his family business. After all, he used to accompany his dad to work on Saturdays as a child, and he keeps photos of his ancestors in the board room. The company has given him a livelihood that supports his family. He has been portrayed in what seems like a fair way by a good young journalist in a major magazine. Plus, the roof continues to support the farm right above him. A century ago, people built factories to last. Mario Balotelli broke down Germany – Germany! – on Thursday.

It was compelling viewing at the center-of-the-Italian universe, Mama’s of Corona, Queens, surrounded by antipasto and cannolis and friends. Three Italophiles – a local hero named Minaya plus a Blum and a Vecsey -- watched Balotelli grow in stature before our eyes. As soon as the big dude blasted his second goal against what had been the strongest-looking team in the Euros, his inner knucklehead could not resist, and he whipped off his jersey, the worldwide macho gesture of goal-scorer pride. Of course, by football regulations, that cost him a yellow card, making him vulnerable to suspension for Sunday’s final against Spain. Still, Balotelli was an impressive sight, a son of Ghanaian immigrants named Barwuah, adopted at 18 by an Italian family, displaying his rippling muscles. “If he scores another goal, they’ll put up a statue of him in Florence,” somebody said. “Il David Nero,” somebody added respectfully in Italian. The Black David. The growth of Balotelli in this tournament has been impressive, a tribute to the man himself and also to Coach Cesare Prandelli, who seems to treat him with calm dignity, neither despairing nor fawning. In the quarterfinals, Prandelli sent Balotelli out first for the penalty kicks against England, and the big guy whacked one past his Man City teammate Joe Hart. If the coach thought he belonged out there…. On Thursday we gathered for the semifinal at Leo’s Latticini, also known as Mama’s, at 46-02 104th St., about a mile south and west of the ballpark I prefer to call New Shea. Ron Blum is a football-soccer expert for the Associated Press; he takes his family to Verona and La Scala every year. I have been an Italy admirer since my first family trip decades ago. And Omar Minaya, son of the Dominican Republic, grew up in the traditionally Italian neighborhood of Corona, dropping into Mama’s when he could afford a sandwich or a biscotto. Later he played two seasons of pro baseball in Italy, and loves to speak the language. Minaya, who now lives in leafy New Jersey, and works in the front office of the San Diego Padres, was on a short home visit for his son's graduation. He remains the favorite son of Mama’s, which has two outlets in the Mets’ ballpark. When he worked nearby, he often ducked over to Mama’s for a snack, a chat, a World Cup match. Anybody who still has a home neighborhood is a lucky person. Although he left after the disastrous season of 2010, this is the kind of guy Omar Minaya is: last year he escorted his successor, Sandy Alderson, to Mama’s –“just to show him the neighborhood, you know,” Minaya explained on Thursday. Mama’s remains the way it has for seven decades, with inevitable changes. The matriarch, Nancy DeBenedettis, passed late in 2009 at the age of 90, but her name lives on. Get this: the official city street sign on the block now says: Mama’s Way. And get this: Public School 16, a few blocks away, has been officially renamed. The Nancy DeBenedettis School. (Read more here about her inspiring American life.) “I get tears in my eyes when I talk about it,” said Irene DeBenedettis, one of three sisters who operate the little empire on Mama’s Way. She was showing me a montage in the window, photos of friends and celebrities who have visited Mama’s. (Half a decade ago, Mario Batali, the celebrity chef, paid the huge compliment of dropping in. (“Mama asked him, ‘Who does your hair?’” Irene said, referring to his iconic ponytail. ) Inside, we were fussed over by Marie DeBenedettis and Carmela Lamorgese, Mama’s two other daughters, and we saw Carmela’s daughter, Marie DiFeo, and her baby, Gina DiFeo, born last Sept. 23, and was wearing an Italia shirt for the Germany match. The staff, from far-flung provinces of Italy, bustled in with cheese, salami, olives, bread, plus pasta with absolutely delicious broccoli rabé, followed by roast beef and potatoes and salad. There might have been a bit of wine, too. Then came the desserts and the coffee. Before the match, we stood and sang the Italian anthem, Il Canto degli Italiani (The Song of the Italians), the most merry anthem in the world. Perhaps we were not as passionate as Gigi Buffon, the Azzurri portiere, who bellows the anthem with his eyes closed, but we tried. Then we remained standing for the German anthem. Oranzo Lamorgese, Gina’s grandfather, is originally from Bari but lived and worked in Hamburg and Dusseldorf for a decade and played semi-pro soccer there. He spoke with great respect for modern Germany – and its football squad. At halftime, Marie DeBenedettis came back and said their deli next door just had a customer – Dwight Gooden himself, buying a hero sandwich. She had invited him to sit with us, but Doc said he was double-parked and didn’t want to get a ticket. We watched as Prandelli wisely removed Balotelli, to protect him from a second yellow card, to preserve him for the final as the Azzurri outlasted Germany, 2-1, to advance safely to the finals. Italy has long produced artful midfielders and defenders who specialize in the defensive catenaccio, the bolt. But now it has a force up front, a striker who is growing in size and tactics, match by match. The three sisters plied the Italophiles named Minaya, Blum and Vecsey with enough love and goodies to last us until Sunday’s final. Mille grazie, amiche mie. My high-school class (Jamaica High, Queens, 1956) is pretty tight. We have held reunions in the old gym and the pizza parlor we used to frequent on Friday nights.

The other day some of us got together in the theater of our dreams, the great Valencia on Jamaica Avenue. Now it is the Tabernacle of Prayer for All People – as awesome as ever. Our class leaders-for-life recently discovered that the Valencia still existed – 3500 seats surrounded by Spanish/Mexican artwork on the walls and ceiling. The only difference, as Sister Forbes, our tour guide, told us, is that some of the statues have been clothed, for modesty’s sake. This theater was one of five first-run emporiums in downtown Jamaica, once the shopping hub for Long Island in the 40’s and early ‘50’s. The Valencia had an orchestra pit and dressing rooms for live Vaudeville shows. My friends seemed to hear the throb of the massive organ. We met on Jamaica Avenue, virtually unrecognizable in daylight. When we were young, the Jamaica El ended at 168th St., but it has long since been torn down. My parents met at the Long Island Press, which went down in 1977. The building is now a Home Depot. We all remembered the glory of downtown Jamaica – the department stores, the cafeterias and clothing stores, but the fondest memories were of the Valencia. Secret smiles indicated great things had happened as James Stewart or Doris Day flickered on the screen. Perhaps the first cigarette in the balcony. Perhaps a first kiss in the dark. The years faded away as we sat in the first couple of rows and listened to Sister Forbes, who told us how the Valencia was opened in January of 1929, designed by the grandiose Loew’s architect, John Eberson. For a New York Times article about the turnaround, please see: http://www.nytimes.com/1990/04/15/realestate/streetscapes-jamaica-s-valencia-theater-success-story-masks-landmarks-law-quirk.html We all knew how movie theaters provided entertainment even during the Depression. And the glamour was there for us during the hope and security of post-war American, as we became old enough to go to the movies by ourselves. For some reason, I could remember going to the Valencia only once – my parents took me to see South Pacific. I remember being out with them more than I remember the glory of the building. My friends supplied the awe and the nostalgia. One of us remembered how a member of his group would hold their places in the ticket line during snowstorms – and how he would repair to an open upstairs room with a stove. Sister Forbes was impressed with his ingenuity. Another of us remembered how one of his party would buy a ticket and then open a side door for his buddies. We didn’t tell Sister Forbes that, lest she cast us out of the tabernacle. Jean White Grenning, our class president for life and captain of the cheerleaders, and Walter Schwartz, the editor of the school paper, recalled the victory rally for the 1955 New York City basketball champions from Jamaica, right there on the stage, as Jean Gollobin’s choir sang. Sister Forbes told us how the Tabernacle was formed when the Valencia closed in 1977. The theater had been reduced to showing “black exploitation” films, she explained, and most of the African-American community wanted no part of that genre. The congregation was larger back in the day, she said. Nowadays around 300 members come to church on Sunday, but sometimes they hold regional services, and the old building rocks again. The good part, she said, was that “things were built to last” in 1929. The congregation has surprisingly little maintenance and repair, she said -- a good thing, I sensed. The building looked great. The congregation does not rent out the building for secular music or other entertainment; we are Pentecostal, Sister Forbes explained. However, they do give tours for a donation, she said. Their number is 718-657-4210. They also welcome worshipers on Sunday -- but not cameras, she added. After a tour of the lobby (some people think the building is gaudy, Sister Forbes said with a proud smile) we said good bye and returned to the bizarre daylight of modern-day Jamaica Avenue. We still expected the rumble of the El. Then we headed toward lunch at a diner on what Walter Schwartz calls Re-Union Turnpike. Stanley Einbender, a star of the 1955-56 basketball team, drove us past Jamaica High, still gorgeous up on the hill. I should add that New York City has cooked the books to come up with spurious excuses for phasing out Jamaica High itself. We are in mourning for a great city institution. That glorious building will accommodate four boutique schools of various or changing description. I have no idea how the ambitious new minorities of Queens can possible navigate all these precious little creations to find a school they can attend. Back then we had big schools, big theaters, big dreams. Our youth was reinforced by a visit to the Valencia, to the Tabernacle. Is there a more foolish display by public officials than the mandatory Super Bowl wager between mayors or governors? Are they so craven that they need the attention?

Phil Taylor of Sports Illustrated, one of the most thoughtful voices among American sports columnists, has a great point this week. He wishes politicians would butt out of sports, particularly those public figures who don’t know a thing about them. Once again, Taylor has done his homework, citing ludicrous examples of politicians who were clearly pandering, out of their element. A rare example of bipartisanship: clearly, over-reaching knows no political boundary. Yet my home town of New York has had two recent mayors who took diametrically opposite positions toward sports, and both worked, for them. Rudy Giuliani made no secret of rooting for his Yankees, whereas Ed Koch had a visceral disinterest in anything sporty. Giuliani wore his Yankee jacket and cap, was a frequent visitor to the Stadium, knew the players, and knew the game. He was delighted that his position as mayor could get him up close to the field. The Yankees won five pennants and four World Series during his regime. He showed up for the sixth game in Arizona in early November of 2001. Given what he had been through back home in the two previous months, he had every right to follow his team. The next morning he was back in New York at the start of the Marathon – another statement that the city would endure, that nihilists and lunatics could not shut us down. Then he flew back to Phoenix for the seventh game that night. “You’re sick,” I said to him in the crush of the deflated clubhouse after the loss. Giuliani understands clubhouse talk. He smiled and shrugged. It was his team, and he was there, to whisper support to Mariano Rivera, to praise the winning team. “''I appreciate the way we were treated,'' Giuliani said. ''And if you have to lose, it's better to lose to a city like this. These people sent us search-and-rescue crews.'' Giuliani would show up at Shea Stadium on opening days or other important moments, pay his respects to the Mets and their fans. But everybody understood. He was a Yankee fan. He had earned that right. Rudy Giuliani was never more appealing than when he rooted for his team. Koch could care less, as we say in New York. He had no interest in sports. If his top aides say, Mr. Mayor, you have to go to opening day, he would allow himself to be whisked out of Manhattan into one outer borough or another, where he would be introduced, endure the obligatory boos, and take a seat for an inning or two. Hizzoner might have stayed longer if the ballparks had included an outpost for some Peking duck emporium. But around the third inning, you would glance down at the box seats, and there would be a gap in the spectators. While the teams changed sides, the mayor had bolted for the exit; the limo was taking him back to the safety and the aromas of downtown. But he never faked it, never talked manly jock talk, never pretended to know who played first base for the Yankees or Mets. I think the estimable Phil Taylor would agree: (strictly in a sports context) if you can’t be Rudy Giuliani, then by all means be Ed Koch. And politicians: have you no dignity? Stop with the wagers. |

Categories

All

|